Live tweeting a presidential primary debate: Comparing the content of Twitter posts and news coverage

Live tweeting a presidential primary debate: Comparing the content of Twitter posts and news coverage

By Kyle Heim

Twitter was a “second screen” during the 2012 U.S. presidential debates as debate viewers shared highlights and observations. This study compared the live Twitter stream during the December 10, 2011, Iowa Republican primary debate with news reports to determine whether the Twitter discussion exhibited the same characteristics as campaign news coverage—emphasizing strategy and media “metacoverage” rather than policy issues. Quantitative and qualitative analyses found that the Twitter discussion focused largely on the role of the ABC News moderators and on Mitt Romney’s offer of a $10,000 bet. Policy issues received less attention on Twitter than in the news reports.

Introduction

Social media are an integral component of modern political campaigns. Candidates use social platforms to disseminate their messages and mobilize supporters. Citizens, meanwhile, use the same platforms to learn about the candidates and share their opinions. According to the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (Rainie & Smith, 2012), 36% of social network site users rate the sites as “very important” or “somewhat important” to them in keeping up with political news, and 25% view the sites as important in debating or discussing political issues with others.

Candidate websites, blogs, YouTube, and Facebook all have played significant roles in recent U.S. presidential elections, but in 2012 it was Twitter, more than any other social network, where the political narrative was formed. As Ashley Parker (2012), who covered the 2012 campaign for The New York Times, explained: “If the 2008 presidential race embraced a 24/7 news cycle, four years later politicos are finding themselves in the middle of an election most starkly defined by Twitter, complete with 24-second news cycles and pithy bursts” (para. 3). Fellow Times political correspondent Jonathan Martin noted that Twitter had become “the real-time political wire. That’s where you see a lot of breaking news. That’s where a lot of judgments are made about political events, good, bad, or otherwise” (Hamby, 2013, p. 24).

Twitter is a microblogging platform that allows a user to post brief messages called “tweets” that may be read by the user’s network of “followers.” One of the most popular uses of Twitter during the 2012 U.S. presidential race was tweeting during the televised candidate debates. More than 10 million tweets were posted during the first general-election debate between Democratic President Barack Obama and Republican challenger Mitt Romney, making the debate the most tweeted-about political event in U.S. history (Sharp, 2012). This “second screen” phenomenon has created a hybrid media environment in which the Twitter conversation, organized around topical “hashtags,” functions as a parallel stream of information alongside the televised debate (Maruyama, Robertson, Douglas, Semaan & Faucett, 2014). Although most participants in the Twitter conversation would not label themselves journalists, the live Twitter stream may be considered a form of ambient journalism (Hermida, 2010), citizen journalism (Murthy, 2011), or alternative journalism (Poell & Borra, 2011) that provides “a constantly updated public source of raw material in near real-time” (Lewis, Zamith & Hermida, 2013, 40).

As news increasingly becomes a “shared social experience” (Purcell, Rainie, Mitchell, Rosenstiel & Olmstead, 2010), it is important for scholars to analyze the content of these social network streams. Much of the research in this vein has analyzed tweets posted during political protests (Papacharissi & de Fatima Oliveira, 2012; Poell & Borra, 2011) or sporting events (Smith & Smith, 2012). Only a few studies have examined live tweeting during a staged political debate, focusing on how live tweeting affects political attitudes and vote choice (Houston, Hawthorne, Spialek, Greenwood & McKinney, 2013; Maruyama et al., 2014) or comparing the conversations of elite and non-elite Twitter users (Hawthorne, Houston & McKinney, 2013).

The present study extends this line of research by comparing the content of tweets posted during the December 10, 2011, Iowa Republican primary debate with news coverage immediately following the debate and with the debate transcript.

Specifically, the study seeks to determine whether the Twitter discussion exhibited the same characteristics as traditional political news coverage.

During the past several decades, U.S. political journalism has shifted from predominantly issue-based coverage to “strategy coverage” about the horse race and the campaign tactics needed for candidates to win, and finally to a third stage of “metacoverage” in which journalists’ stories focus on the media’s role in political affairs (Esser & D’Angelo, 2003; Esser, Reinemann & Fan, 2001; Johnson, Boudreau & Glowaki, 1996; Patterson, 1993). This shift toward more strategic stories and metacoverage has been blamed for an increase in the public’s political cynicism (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; de Vreese & Elenbaas, 2008). Additionally, debate coverage has been faulted for emphasizing negative candidate attacks rather than positive messages (Benoit, Stein & Hansen, 2004; Reber & Benoit, 2001). Twitter may be a partial remedy for some of these problems, elevating the political discourse by offering debate viewers a forum to discuss substantive issues. Or it may exacerbate the ills of traditional political journalism, encouraging negativity and a focus on the trivial.

The present study uses both quantitative and qualitative analysis of the Twitter stream, the news coverage, and the transcript of the Iowa Republican debate to compare the content of each source. Centering resonance analysis (CRA), a computer-assisted, network-based form of text analysis, is used to map relationships in the discourse by isolating influential words and word pairs (Corman & Dooley, 2006). This method is coupled with a qualitative textual analysis to identify central themes in the discourse.

Literature Review

Presidential Primary Debates

Televised presidential debates are an American political tradition, with an unbroken string of such encounters since 1976. Best and Hubbard (1999) identified three normative functions of candidate debates: engaging viewers in the campaign by highlighting the election stakes and participants, educating viewers about the issues, and informing viewers about the candidates and their qualifications. The primary season, when the Republican and Democratic parties narrow the field of candidates, represents the best time to fulfill those functions because many candidates are still largely unknown, issue agendas and policy positions are still taking shape, and voters’ attitudes are susceptible to change. Experimental research has linked watching primary debates to a greater likelihood of participating in the primary, increased learning about the candidates’ policies, and changes in citizens’ voting intentions and evaluations of the candidates (Benoit, McKinney & Stephenson, 2002; Best & Hubbard, 1999; Yawn, Ellsworth, Beatty & Kahn, 1998).

A separate body of research has examined the content and tone of candidates’ messages during primary debates. Benoit, Henson, and Sudbrock (2011) analyzed the 2008 Democratic and Republican primary debates using the Functional Theory of Political Campaign Discourse, which posits that candidates may demonstrate their desirability for office by praising themselves (acclaims), criticizing their opponents (attacks), or responding to an opponent’s attack (defenses). Their content analysis found that both the Republicans and Democrats favored acclaims over attacks by a wide margin (67% to 27% for Democrats and 68% to 24% for Republicans), with defenses representing only a fraction of both parties’ debate themes. The researchers also compared the debate discussion of policy issues and candidates’ character, concluding that issues dominated the debate messages of both the Republican and Democratic candidates (72% to 28% for Democrats and 67% to 33% for Republicans). Thus, political communication research has found primary debates to be largely positive in tone, substantive in nature, and effective in educating the electorate.

News Coverage of Presidential Politics

Even if the candidates strive to present positive, issue-oriented messages during a presidential primary debate, their efforts may be frustrated by other actors in the political process. Jackson-Beeck and Meadow (1979) observed the interplay of three agendas in presidential debates: the agendas of the candidates, the journalists, and the voters.

These three agendas have not always been in sync, according to the researchers’ comparison of debate transcripts with polling data. For example, journalists’ questions during the debates generally did not correspond with the issues that the public thought were most important.

The incongruity between the agendas of the journalists and the public is not surprising given that news coverage has never been a true mirror of reality. Studies of the sociology of news have shown that journalists, through their individual and institutional routines, actively filter and shape reality rather than merely reflecting it. News is socially constructed (Tuchman, 1978), a pseudo-environment that exists in between “the world outside” and “the pictures in our heads” (Lippmann, 1922). Journalists “frame” the news by choosing which aspects of reality to make most salient in their stories (Entman, 1993). News stories thus “become a forum for framing contests in which political actors compete by sponsoring their preferred definitions of issues” (Carragee & Roefs, 2004, p. 216).

In the case of political reporting, journalists’ framing of presidential campaigns has changed dramatically during the past half-century. In the 1960s, the candidates were the main agenda setters, and news coverage emphasized their policy statements (Esser et al., 2001; Kerbel, 1994; Patterson, 1993). By the 1970s, in the wake of the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal, campaign reporting had taken a turn toward “strategy coverage,” marked by six characteristics: (1) winning and losing as the main concern; (2) the language of wars, games and competition; (3) a story with plots, performers, critics and audience (voters); (4) centrality of performance, style, maneuvers, and manipulated appearances of the candidate; (5) journalists’ interpretation and their questioning of candidates’ motives; and (6) emphasis on opinion polls (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997, p. 33).

Finally, 1988 saw the birth of a third stage of election reporting known as “metacoverage,” focused on the media’s role as a political actor. Metacoverage may take two forms: (1) “self-coverage,” in which journalists treat themselves as the subjects of their own political stories; and (2) “process news” or “publicity metacoverage” about campaign operatives’ attempts to influence or manipulate the media, such as through political advertising and “spin doctors” (de Vreese & Elenbaas, 2008; Esser et al., 2001).

The shift from issue-based stories to strategic coverage and metacoverage has been blamed for arousing political cynicism in the electorate, although research findings have not been uniform. Cappella and Jamieson (1997) concluded that the media’s framing of political campaigns in strategic terms leaves an impression that politicians are motivated by power, not the public good, creating a “spiral of cynicism” that alienates citizens from politics. Similarly, in experiments by de Vreese and Elenbaas (2008), individuals who read newspaper stories featuring strategy coverage or publicity metacoverage reported higher levels of political cynicism than those who read stories focusing on issue substance. Individuals who read stories featuring press self-coverage also reported higher levels of cynicism, but the difference was not significant.

By contrast, an examination of media-related newspaper and television stories from the 1992 presidential campaign revealed that most of the stories contained only general mentions of the media, such as listings of candidates’ TV appearances, rather than discussion of media strategy or performance (Johnson, Boudreau & Glowaki, 1996).

The researchers concluded that “fears that coverage of the media is increasing voter cynicism by portraying politicians as self-interested media manipulators and journalists as willing dupes in the manipulation process may be overstated” (Johnson et al., 1996, p. 665).

Studies of presidential debate coverage have not typically focused on strategy coverage or metacoverage, but researchers have analyzed the tone of coverage by comparing the proportions of candidate acclaims and attacks. Benoit et al.’s (2004) comparison of the content of general-election debates from 1980 to 2000 and newspaper coverage of the debates found that even though acclaims were more common than attacks during the debates (61% to 31%), newspaper stories featured the opposite pattern (41% to 50%), suggesting to readers that the debates were more negative than they actually were. A separate study of two primary debates—one Republican and one Democratic—during the 2000 presidential election and corresponding coverage in The New York Times, reached the same conclusion: Whereas the candidates emphasized acclaims, the Times‘ articles emphasized attacks (Reber & Benoit, 2001).

The difference in tone between news coverage and the debates themselves is especially worrisome given the news media’s ability to influence voters, even those who watch the debates themselves. One experiment (Fridkin, Kenney, Gershon, Shafer & Woodall, 2007) in which participants watched a 2004 presidential debate between George W. Bush and John Kerry revealed how journalists’ analysis can change public perception. Subjects who watched the debate and listened to NBC News’ post-debate analysis, which was largely favorable toward Bush, rated Bush more favorably on an assortment of trait and affect assessments. On the other hand, those who watched the debate and read CNN.com’s online analysis, which gave Kerry more positive treatment, rated Kerry more favorably (Fridkin et al., 2007).

Twitter and the Voice of the People

Unlike journalists, who process political information through a “strategic schema” and view candidates as strategic actors, the public uses a “governing schema” to focus on how governmental decisions will affect their everyday lives (Patterson, 1993, p. 59).

There are indications that the public is demanding a more substantive form of political journalism that corresponds with their governing schema. In a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center for People and the Press during the 2008 presidential campaign, “candidates’ positions on issues” and “candidate debates” were the top topics that the public wanted covered more—77% wanted more issue coverage and 57% wanted more debate coverage (Project for Excellence in Journalism, 2007).

There also are indications, however, of a gap between what citizens say they want in political coverage and the kinds of news stories they actually choose to consume.

Trussler and Soroka (2014) found that even people who indicated on a survey that they wanted to read positive political stories tended to select negative stories when presented with a choice. The researchers suggested that the media’s focus on negative and strategy-based political coverage may be, at least in part, a response to public demand.

Traditionally, the electorate had little voice in presidential campaigns. Members of the public assumed the role of debate spectators as journalists crafted the questions to be asked of the candidates. That began to change in 1992 with the introduction of the town hall debate format, which allowed citizens to question the candidates directly. McKinney (2005) found that the issue agenda of the 1992 and 2004 town hall debates strongly correlated with opinion polls measuring the public’s most important issues, leading him to conclude that citizens “have demonstrated their ability to perform an important function in the debate exchange” (p. 209). Even in the town hall debates, however, the candidates and the media still retained considerable control over the proceedings (McKinney, 2005).

An even more significant development than the town hall debate format was the introduction of social networking sites such as Facebook and YouTube, beginning with the 2008 presidential campaign. These new communication technologies transformed online spaces from mouthpieces that amplify candidate messages into participatory spaces that function as a “digital agora” (Kirk & Schill, 2011, p. 326).

By 2012, the microblogging site Twitter had become the primary social network site for discussing the U.S. presidential race, and it was used by the campaigns, journalists, and seemingly everybody else. Twitter was first made available to the public in August 2006, and by the third quarter of 2014 the microblogging service had 284 million average monthly active users (“Twitter reports third quarter 2014 results,” 2014). Twitter users may post messages of 140 characters or fewer, which can spread quickly through the Twittersphere via the practice of retweeting, in which a user forwards the tweet to his or her followers. This network structure suggests the possibility of a more democratic and egalitarian form of news distribution than traditional journalism. As The Washington Post stated in an article about the 2012 presidential race: “The old journalistic hierarchy that once aggrandized major newspapers and national networks has flattened out, giving any boy, girl or baby on the bus with a Twitter feed the same opportunity to drive the race as the most established brand names” (Horowitz, 2012, para. 4).

Several scholars have explored the relationship between Twitter and journalism. Although Twitter is not a news site run by journalists, it is often quicker than traditional news sites in capturing breaking news (Sankaranarayanan, Samet, Teitler, Lieberman & Sperling, 2009). Eyewitnesses can tweet firsthand accounts from the scene of a major news event in real time. Murthy (2011) argued that Twitter “has at its disposal a virtual army of citizen journalists ready to tweet at a moment’s notice” (p. 783). Hermida (2010) regards Twitter as a form of ambient journalism, considering the microblogging platform to be an “awareness system” whose value rests less with the contents of individual tweets than with the overall portrait created by accumulated tweets over time (p. 301). Twitter has been likened to both a newswire, because it provides continually updated raw information, and to a newsroom, because serves as a site for evaluating, verifying, and highlighting relevant information (Lewis, Zamith & Hermida, 2013).

Papacharissi and de Fatima Oliveira (2012) examined the nature of news storytelling on Twitter by analyzing tweets posted during the Egyptian uprisings of 2011. They found that the Twitter stream reflected traditional news values such as proximity and conflict, as well as four news values unique to Twitter: instantaneity, crowdsourced elites, solidarity, and ambience. The researchers characterized the Twitter discussion as affective in the way it blended news, opinion, and emotion to a degree that it was impossible to separate one from the other. Poell and Borra (2011) studied tweets, along with videos and photos posted to YouTube and Flickr, as a form of alternative journalism during the protests at the 2010 Toronto G20 summit. In many ways, the Twitter stream resembled often- criticized mainstream journalistic practices, such as a focus on police activities rather than the reasons behind the protests. Although a small number of sources dominated on all three forms of social media, Twitter showed more evidence of crowdsourcing than the other two sites due to the practice of retweeting (Poell & Borra, 2011).

Twitter as a Second Screen

One popular use of Twitter is as a second screen during live television events. According to a Nielsen (2013) survey, nearly half of smartphone and tablet computer owners use their devices as second screens while watching TV every day. The phone or tablet is used most frequently for web searching and browsing, but 21% of tablet owners and 18% of smartphone owners said they read conversations about the TV program on social networking sites. Smith and Smith (2012) found that these conversations helped build identity and community by creating a “virtual watercooler” during the final games of the 2012 College World Series of Baseball. Participants in the Twitter discussion about the baseball series maintained game commentaries and used Twitter as a site for celebration, cheering and encouragement, as well as for jeering and taunting the opposing team (Smith & Smith, 2012).

Only a few studies have examined live tweeting of political debates. Maruyama et al. (2014) found that Twitter users who actively tweeted during a debate were significantly more likely to change their vote decision immediately after the debate than those who simply monitored the Twitter stream or did not use Twitter at all. Similarly, Houston et al. (2013) found that live tweeting during a 2012 presidential debate was associated to changes in perceptions of Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. In one of the few studies to analyze the content of tweets, Hawthorne et al. (2013) found little difference in the issues discussed by elite and non-elite Twitter users during a 2012 primary debate.

The present study extends this line of research by comparing discussion on Twitter during an Iowa Republican primary debate in the 2012 U.S. presidential campaign with news coverage and the debate itself. Two research questions are posed:

RQ1: How did the Twitter stream from the Iowa primary debate compare with news coverage and the debate itself in the discussion of policy and character?

RQ2: How did the Twitter stream from the Iowa primary debate compare with news coverage in the use of strategy coverage and media-focused metacoverage?

Method

This study used a combination of quantitative centering resonance analysis (CRA) and qualitative textual analysis to study the Twitter conversation during the December 10, 2011, Iowa Republican primary debate and compare it to mainstream news coverage and the candidates’ debate statements.

Sampling

The December 10, 2011, Republican primary debate took place at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, and was sponsored by ABC News, The Des Moines Register, and the Republican Party. This debate was selected as the research focus for several reasons. First, political scholars have observed that primary debates, occurring early in the campaign season, have a strong potential to influence voters because many candidates are still largely unknown and many citizens are still undecided about whom to support. Because all of the candidates are from the same political party, debate viewers are forced to look beyond party identification to distinguish among the candidates and evaluate their performance. Thus, it was expected that the Twitter discussion would rise above simple partisan bickering. Finally, the debate occurred while the GOP race was still wide open. It featured six candidates—Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, Rick Perry, Michele Bachmann, Rick Santorum, and Ron Paul—ensuring a diversity of viewpoints and a lively exchange. The weeks preceding the first-in-the-nation Iowa caucuses are crucial in the presidential race because candidates who do better than expected in the state may see a burst of momentum while those who fare poorly may see their electoral chances slip away (Mayer & Busch, 2004).

Tweets were collected from 8 p.m. Central time, when the debate started, until 10:30 p.m., about a half-hour after the debate had concluded. The tweets were located by performing a Twitter search for all tweets containing the hashtags #RepublicanDebate, #GOPDebate, and #IowaDebate and refreshing the search throughout the evening. The process yielded a total of 3,032 tweets. This total obviously does not include all tweets related to the debate, such as those that did not use one of the three hashtags, but it provided a large and diverse enough sample to assess the overall content and tone of the Twitter stream.

ABC News posted a full transcript of the debate online, which was used to analyze the content of the debate.

Finally, the main debate news story was collected from the websites of each of the three leading U.S. newspapers known for their coverage of national politics (The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times), from two major wire news services whose stories appear across the nation and the world (The Associated Press and McClatchy Newspapers), and from the website of the debate host city’s newspaper (The Des Moines Register). These stories, representing a purposive sample of debate news coverage, were obtained at approximately midnight Central time, about two hours after the debate had ended, in order to collect immediate news coverage rather than “next-day” stories that might appear the following morning.

Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

Following the recommendations of Lewis et al. (2013) for the content analysis of large datasets, this study used a hybrid approach that combined computational analysis, designed to identify patterns in the data that the researcher might otherwise miss, and manual analysis, which is more sensitive to context and latent textual meanings.

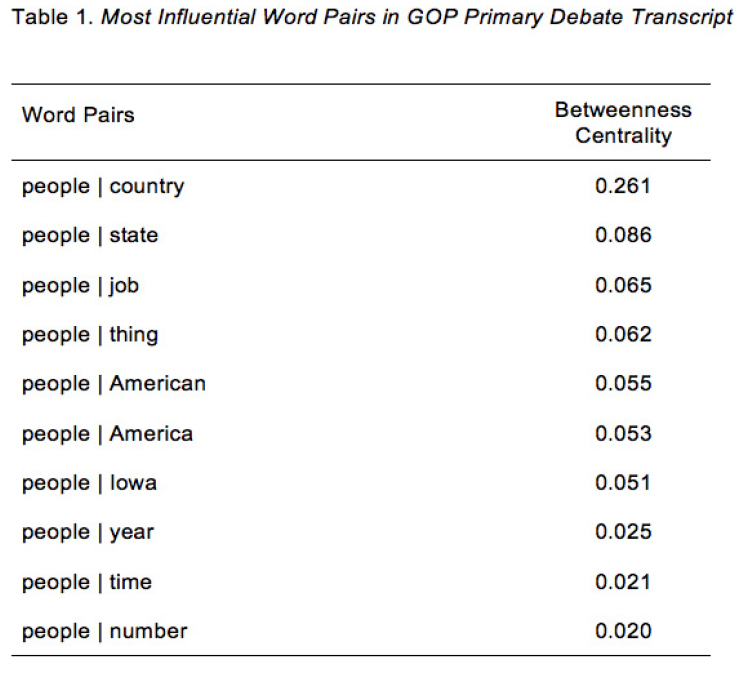

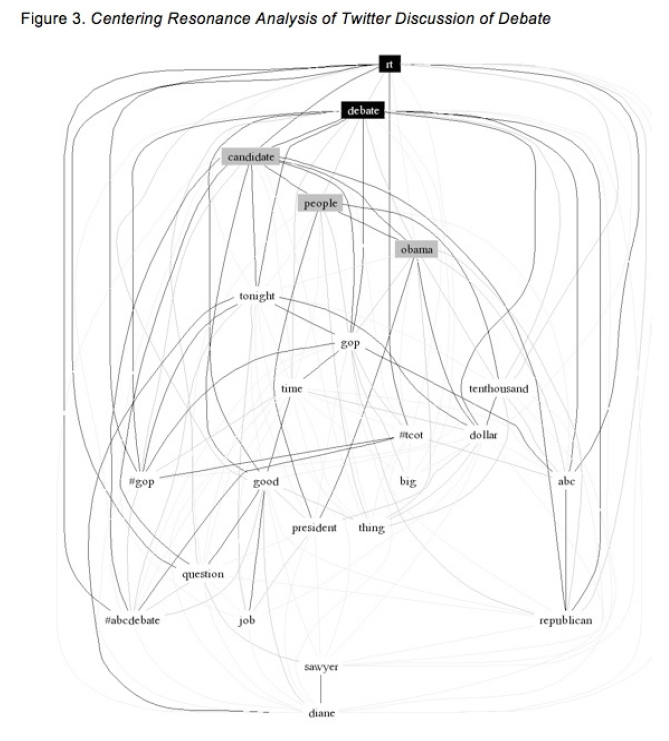

The tweets, news articles, and debate transcript were each analyzed separately using Crawdad Text Analysis software, which performs centering resonance analysis (CRA), a method of studying large sets of texts to identify the most influential words that link other words in the network (Corman & Dooley, 2006). Unlike traditional computational methods based solely on word frequency, CRA is able to isolate influential words that create coherence in a text network (Crawdad Technologies LLC, 2010). The influence of a word is determined by measuring its betweenness centrality—“its likelihood of being on the shortest path in the network connecting any other two words” (McPhee, Corman, & Dooley, 2002, p. 276). Results are presented as maps showing the associations between words and as lists of the most influential words and word pairs and their betweenness-centrality measures (McPhee, Corman, & Dooley, 2002).

CRA has been used by researchers to study the framing of terrorism in U.S. and United Kingdom newspapers (Papacharissi & de Fatima Oliveira, 2008), crisis communication strategies used in the speeches of the CEO of tobacco company Phillip Morris (de Fatima Oliveira & Murphy, 2009), and similarities and differences between corporate ethics codes (Canary & Jennings, 2008). It also has been used to analyze Twitter conversations, including tweets related to the Egyptian uprisings (Papacharissi & de Fatima Oliveira, 2011) and the use of Twitter by public relations professionals as part of the professional identity construction process (Gilpin, 2011). Thus, its validity as a research tool has been established.

When performing the CRA, rules were created to exclude words that were likely to be influential but were not meaningful for research purposes. The first and last names of the candidates were excluded, as were titles such as “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” “Sen.,” and “Gov.,” and the three hashtags #GOPDebate, #RepublicanDebate, and #IowaDebate.

The results of the CRA helped guide the qualitative textual analysis, in which the researcher read the debate-related Twitter stream, the news stories, and the debate transcript several times in an effort to identify key themes regarding the content and tone of the discussion. Qualitative textual analysis enables the researcher to look beyond the manifest content of media messages to consider patterns of latent meaning (Fürsich, 2008). In presenting the findings of the textual analysis, tweets are reproduced in their original form, including any spelling, grammar, or punctuation errors.

Results

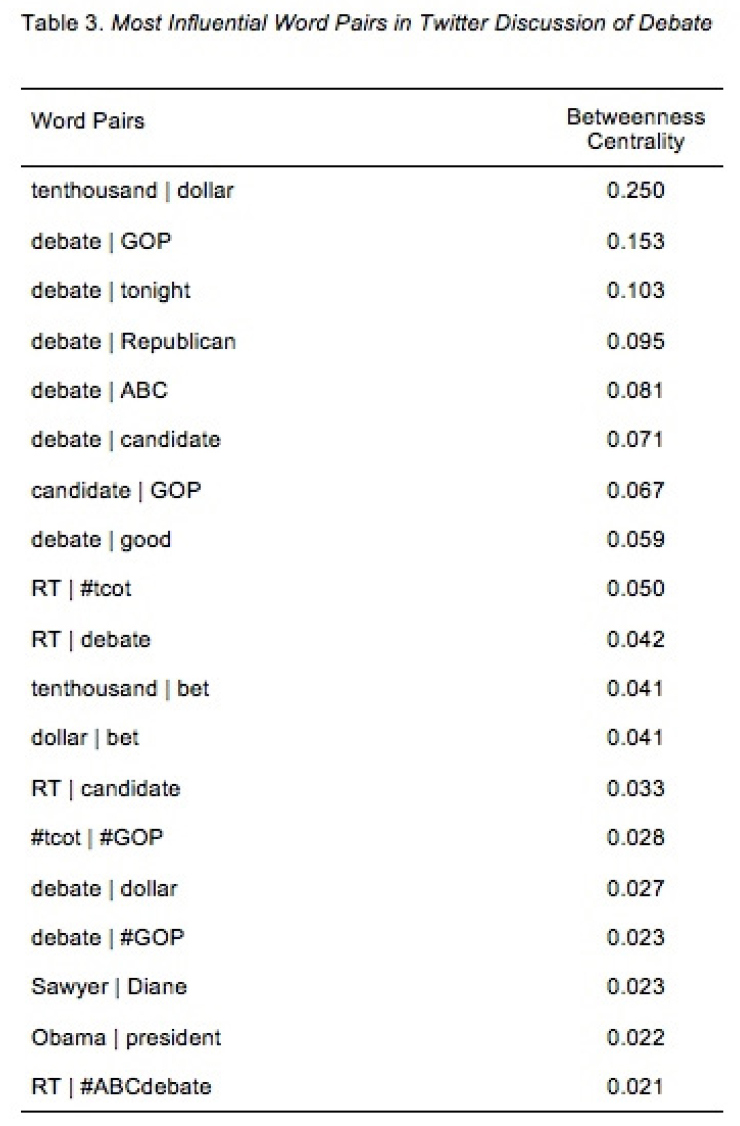

Figures 1, 2, and 3 map the associations of the most influential words in the debate transcript, news coverage, and Twitter stream, respectively. For each source, the most influential words appear in black boxes, other words with very high influence appear in gray boxes, and less influential words are unboxed. Lines show the associations among words, with darker lines indicating stronger levels of association. Tables 1, 2, and 3 list the word pairs that were most influential in each of the three sources, along with their corresponding betweenness centrality values. Betweenness centrality values range from 0 to 1. Values of .01 or greater are considered significant (Corman & Dooley, 2006).

Figures 1, 2, and 3 map the associations of the most influential words in the debate transcript, news coverage, and Twitter stream, respectively. For each source, the most influential words appear in black boxes, other words with very high influence appear in gray boxes, and less influential words are unboxed. Lines show the associations among words, with darker lines indicating stronger levels of association. Tables 1, 2, and 3 list the word pairs that were most influential in each of the three sources, along with their corresponding betweenness centrality values. Betweenness centrality values range from 0 to 1. Values of .01 or greater are considered significant (Corman & Dooley, 2006).

For this study, a value of .02 was used as the cutoff point in order to keep the number of influential words and word pairs to a manageable size and make the data easy to visualize.

According to the CRA maps, “people” was the most influential word in the debate transcript, suggesting that the candidates sought to humanize their messages and appeal to the television audience. Not surprisingly, the word “debate” was most influential in the news coverage, indicating that journalists focused their coverage on the event itself. The word “debate” also was highly influential in the Twitter stream, suggesting that the tweets also exhibited a strong event-based focus, as was “RT,” an abbreviation for retweet. Retweeting was a common practice throughout the debate as Twitter users forwarded information they found particularly insightful or humorous.

RQ1 asked how the Twitter stream compared with news coverage and the debate itself in the discussion of policy and character. An examination of the CRA maps, along with the lists of influential word pairs, shows that policy issues were featured prominently in the debate and the subsequent news coverage, but not in the Twitter discussion. In the debate transcript and the news coverage, but not in the tweets, the word “issue” was highly influential, appearing in a gray box in both CRA maps. In the debate transcript, the words “Palestinian,” denoting discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and “money” and “tax,” signaling discussion of economic matters, also were influential. Interestingly, policy issues were even more prominent in the news coverage, where such words as “economy,” “Freddie Mac,” “Palestinian,” “Israel,” and the combination of “health” and “care” were among the most influential. In fact, the pairing of “health” and “care” was among the most influential word pairs in the news articles. By contrast, no issue-related words were among the most influential within the Twitter stream.

This does not mean, however, that the Twitter conversation was devoid of policy matters. Qualitative analysis of the stream revealed that Twitter users did mention some policy issues, but not necessarily the ones being debated. Rather than adhering to the issue agenda set by the moderators and the candidates, Twitter users treated the microblogging platform as a forum to discuss issues personally important to them. Several tweets took the form of personal pleas to the candidates or moderators to address issues that were being neglected:

Why can’t they address ‘student debt’ instead as opposed to ‘faith’ in the #iowadebate. Let’s get down to business.

Gov. Perry, how will you protect homeschooling families when you become president. #IowaDebate

ask candidates their thoughts on the stock act and how they feel about law makers placing trades on inside info #iowadebate

Turning to the matter of candidate character, the CRA revealed no influential character-related words for the debate transcript. The map for the news coverage, however, revealed a strong association between the words “former” and “wife,” a reference to Newt Gingrich’s history of marital infidelity. This topic arose when one of the debate moderators asked whether voters should consider whether a candidate has been faithful to his or her spouse when deciding whom to support for president.

On Twitter, the combination of “tenthousand” (treated as a single word for purposes of the CRA) and “dollar” was the most influential word pair within the stream. Other combinations of those words together with “bet” also were highly influential. These words refer to a moment during the debate when Mitt Romney leaned over to Rick Perry and offered to bet $10,000 over their differing views on whether Romney had shifted his position on a health care mandate. Perry declined the offer. To users on Twitter, the exchange spoke to Romney’s character, suggesting that he was a wealthy man who was out of touch with ordinary citizens:

Why the hell is Mitt betting 10k, during a debate? Way to be an everyman, Mitt. #1percenter. #gopdebate #IowaDebate #tcot

Nothing says I relate the the American people @MittRomney like trying to make a $10,000 dollar bet on national TV #iowadebate

Mitt Romney may have lost the nomination on a #10kbet that nobody actually took. #iowadebate

The discussion quickly caught fire on Twitter and remained a hot topic throughout the evening. A Democratic Party operative would later create a Twitter hashtag,

#What10KBuys, to capitalize on Romney’s apparent faux pas and keep the discussion going.

Interestingly, the bet offer was not mentioned at all in three of the six news articles (though it would later be discussed in stories the following day). In those articles in which it was mentioned, it was not referenced until the 12th paragraph or later and received only brief attention. For example, The Des Moines Register article referred to it only in passing:

Romney, who had earlier in the debate challenged a rival to a $10,000 bet, said he did not grow up poor, though his father did. He said his father passed on the values of hard work and smart spending. He also talked of his Mormon faith, noting he served the less fortunate overseas through his church.

RQ2 asked how the Twitter stream compared with news articles in the use of strategy coverage and media-focused metacoverage. Quantitative and qualitative analyses revealed that both the news articles and the Twitter stream contained elements of strategy coverage or media-focused metacoverage, but there were differences in the forms that it took.

In the news articles, strategy coverage was clearly seen in the emphasis on polls and the horse-race aspect of the campaign. “Poll,” “rival,” and “attack” appeared as highly influential words in the CRA map. All six of the news articles focused on Gingrich in the lead paragraph, noting his new status as the GOP front-runner after Iowa and national polls had shown him seizing the lead from Romney. For example, the Los Angeles Times story began with a strategy focus:

With Newt Gingrich as their common target, the Republican presidential hopefuls piled on the new party front-runner in a lively debate Saturday night, jabbing him over his political consistency, the sturdiness of his character and the plausibility of his policy proposals.

Strategy coverage in the Twitter stream, on the other hand, focused on the stagecraft and performance aspects of the debate. Twitter users noted, for example, that the candidates did not do the traditional introductory “pageant walk” to enter the stage. Several users commented that the debate stage resembled the set of the game show “Jeopardy.” The debate also was likened to a circus in which the candidates were the clowns. Candidate appearance was another popular topic of discussion, with several Twitter users noting that all of the male candidates except Romney wore red ties.

The Twitter stream, unlike the news articles, also contained a great deal of media-focused “metacoverage,” suggesting that in the eyes of Twitter users, the debate was more a media-created event than a political dialogue. Much of the Twitter discussion focused on the performance of the ABC News moderators, Diane Sawyer and George Stephanopolous. “ABC,” the hashtag “#ABCdebate,” and the combination of “Diane” and “Sawyer” appeared in the CRA map of influential words and in the list of influential word pairs. Sawyer was a favorite target, drawing much criticism for her demeanor and her lines of questioning:

Diane Sawyer is a horrible moderator. Holy crap I’m irritated. Really irritated is a nice way to put it #iowadebate #abcdebate

The moderators 4 the GOP debates are out of touch with the American People as the candidates. I expected better, Diane Sawyer. #IowaDebate

WHY is Diane Sawyer so condescending? It’s a room full of adults, not a bunch of urchins pulled out of the reform school. #IowaDebate

Diane Sawyer’s questions are meandering all over the place. #iowadebate

In addition to frustration with Sawyer, some Twitter users expressed frustration with the news media in general:

@elainetangerine That’s what you get with TV. No depth. #IowaDebate

Could the media Manipulation get any more obvious? So much about Newt G, Ron Paul clearly won this debate #IowaDebate

Discussion

News coverage of U.S. presidential elections has been faulted for fostering political cynicism by emphasizing campaign strategy and the role of the media rather than in-depth discussion of policy issues. This study sought to determine whether the ambient journalism on Twitter exhibits the same characteristics. The study compared the tweets posted during a Republican primary debate in the 2012 presidential campaign with news stories published shortly after the debate.

Quantitative and qualitative analyses revealed that the Twitter discussion was far less substantive than the coverage found on the websites of leading newspapers and wire services. Whereas the news reports stayed faithful to the debate, addressing the issues raised by the candidates and moderators, the Twitter stream was dominated by comments about the staging of the event, candidate appearance, and the performance of the journalist moderators. Arguably trivial matters, such as Mitt Romney’s remark challenging Rick Perry to a $10,000 bet, became focal points of discussion while policy matters received scant attention.

It is impossible to generalize based on a study of one debate involving one political party during one election cycle. But if the tweets posted during the Iowa debate are indicative of wider political discussion on Twitter, the microblogging platform might magnify, rather than alleviate, the problems associated with mainstream news coverage of presidential campaigns. This finding is in line with other studies that have shown Twitter perpetuates often-criticized journalistic practices, such as Poell and Borra’s (2011) finding that tweets during the protests at the 2010 Toronto G20 summit focused more on police activities than on the reasons behind the protests.

To be fair, most Twitter users make no claim to be journalists and are under no obligation to be fair or balanced while tweeting about a news event such as a presidential debate.

Furthermore, the 140-character limitation of tweets makes in-depth analysis of policy matters almost impossible. The Twitter second screen, then, is a highly eclectic collection of small bits of information, both serious and frivolous, substantive and trivial. This can be problematic when Twitter becomes a “first screen”—a substitute for witnessing an event or for reading or viewing subsequent news reports. Several people who posted on Twitter during the Iowa primary debate indicated that they believed Twitter could provide all they needed to know about the presidential debate:

Not watching the debate, will follow the #iowadebate hashtag

Glad I have @BorowitzReport and @TheInDecider to provide me balanced coverage of #RepublicanDebate since there’s no way I’m watching it.

These individuals who relied exclusively on Twitter would have received a highly skewed version of the debate that was missing critical details. Furthermore, given the Twitter stream’s heavy focus on strategy and metacoverage, these individuals might have come away feeling more cynical about the Republican candidates or presidential politics in general. Twitter certainly provides a valuable forum for sharing observations about political events in real time, but it does not yet appear to be a substitute for traditional journalism. Some form of editorial “gatekeeping” or “curating” is still needed to evaluate information and add context and perspective.

Although the content of the Twitter discussion raises some causes for concern, it also hints at the possibility of positive changes in politics and journalism. Many of the tweets about the Iowa debate were snarky or even rude, but they often carried a serious message, serving as a critique of the debate format, the media’s performance, and the artificiality of the event. In an era of open, participatory media, Twitter users lashed out at the contrived nature of the debate, the tight control over the event by the candidates and moderators, the lack of attention to issues that truly matter to voters, and a general lack of authenticity. Politicians and journalists would do well to heed such criticism.

Perhaps the freewheeling discussions on social media ultimately will produce changes in the presidential debate format, giving citizens a greater voice and more opportunities to engage with the candidates. Social media also might help usher in a new era of political news coverage. If the first era of political coverage focused on the candidates’ issues, the second era on the candidates’ strategies, and the third era on the role of the media in the political process, perhaps Twitter and other social media signal the beginning of a fourth era focused directly on the voters and their priorities. Researchers might consider surveying or interviewing political journalists to determine whether they monitor social media to gauge voter opinion and how that influences the content of the stories they produce.

References

Benoit, W. L., Henson, J. R., & Sudbrock, L. A. (2011). A functional analysis of 2008 U.S. presidential primary debates. Argumentation and Advocacy, 48(2), 97-110.

Benoit, W. L., McKinney, M. S., & Stephenson, M. T. (2002). Effects of watching primary debates in the 2000 U.S. presidential campaign. Journal of Communication, 52(2), 316-331.

Benoit, W. L., Stein, K. A., & Hansen, G. J. (2004). Newspaper coverage of presidential debates. Argumentation and Advocacy, 41(1), 17-27.

Best, S. J., & Hubbard, C. (1999). Maximizing “minimal effects”: The impact of early primary season debates on voter preferences. American Politics Research, 27(4), 450-467.

Canary, H. E., & Jennings, M. M. (2008). Principles and influence in codes of ethics: A centering resonance analysis comparing pre- and post-Sarbanes-Oxley codes of ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(2), 263-278.

Cappella, J. N. & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carragee, K. M. & Roefs, W. (2004). The neglect of power in recent framing research. Journal of Communication, 54(2), 214-233.

Corman, S., & Dooley, K. (2006). Crawdad text analysis system. Chandler, Arizona: Crawdad Technologies, LLC.

Crawdad Technologies LLC (2010). Crawdad text analysis software. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from https://web.archive.org/web/20131011082532/http://www.crawdadtech.com/

de Fatima Oliveira, M., & Murphy, P. (2009). The leader as the face of a crisis: Philip Morris’ CEO’s speeches during the 1990s. Journal of Public Relations Research, 21(4), 361-380.

de Vreese, C. H., & Elenbaas, M. (2008). Media in the game of politics: Effects of strategic metacoverage on political cynicism, Press/Politics, 13(3), 285-309.

Entman, R. E. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58.

Esser, F., & D’Angelo, P. D. (2003). Framing the press and the publicity process: A content analysis of meta-coverage in Campaign 2000 network news. American Behavioral Scientist, 46(5), 617-641.

Esser, F., Reinemann, C., & Fan, D. (2001). Spin doctors in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany: Metacommunication about media manipulation. Press/Politics, 6(1), 16-45.

Fridkin, K. L., Kenney, P. J., Gershon, S. A., Shafer, K., & Woodall. G. S. (2007). Capturing the power of a campaign event: The 2004 presidential debate in Tempe. The Journal of Politics, 69(3), 770-785.

Fürsich, E. (2008). In defense of textual analysis: Restoring a challenged method for journalism and media studies. Journalism Studies, 10(2), 238-252.

Gilpin, D. R. (2011). Working the Twittersphere. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites. New York: Routledge.

Hamby, P. (2013, September). Did Twitter kill the Boys on the Bus? Searching for a better way to cover a campaign. Joan Shorenstein Center. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/d80_hamby.pdf

Hawthorne, J., Houston, J. B., & McKinney, M. S. (2013). Live-tweeting a presidential primary debate: Exploring new political conversations. Social Science Computer Review, 31(5), 552-562.

Hermida, A. (2010). Twittering the news: The emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practice, 4(3), 297-308.

Horowitz, J. (2012, October 30). For campaigns’ traveling press corps, social media has changed way game is played. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/decision2012/for-campaigns-traveling-press-corps-social-media-haschanged-way-game-is-played/2012/10/30/32b0ceea-2299-11e2-ac85-e669876c6a24_story.html

Houston, J. B., Hawthorne, J., Spialek, M. L., Greenwood, M., & McKinney, M. S. (2013). Tweeting during presidential debates: Effect on candidate evaluations and debate attitudes. Argumentation and Advocacy, 49(4), 301-311.

Jackson-Beeck, M., & Meadow, R. G. (1979). The triple agenda of presidential debates. Public Opinion Quarterly, 43(2), 173-180.

Johnson, T. J., Boudreau, T., & Glowaki, C. (1996). Turning the spotlight inward: How five leading news organizations covered the media in the 1992 presidential election. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(3), 657-671.

Kerbel, M. R. (1994). Edited for television: CNN, ABC, and the 1992 presidential campaign. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Kirk, R., & Schill, D. (2011). A digital agora: Citizen participation in the 2008 presidential debates. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(3), 325-347.

Lewis, S. C., Zamith, R., & Hermida, A. (2013). Content analysis in an era of Big Data: A hybrid approach to computational and manual methods. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(1), 34-52.

Lichter, R., & Smith, T. (1996). Why elections are bad news: Media and candidate discourse in the 1996 presidential primaries. Press/Politics, 1(4), 15-35.

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York: Free Press Paperbacks.

Maruyama, M., Robertson, S. P., Douglas, S. K., Semaan, B. C., & Faucett, H. A. (2014). Hybrid media consumption: How tweeting during a televised political debate influences the vote decision.

In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing, 1422-1432.

Mayer, W. G., & Busch, A. E. (2004). The front-loading problem in presidential elections. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

McKinney, M. (2005). Let the people speak: The public’s agenda and presidential town hall debates. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(2), 198-212.

McPhee, R. D., Corman, S. R., & Dooley, K. (2002). Organizational knowledge expression and management. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 274-281.

Murthy, D. (2011). Twitter: Microphone for the masses? Media, Culture & Society, 33(5), 779-789.

Nielsen (2013, June 17). Action figures: How second screens are transforming TV viewing. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2013/actionfigures–how-second-screens-are-transforming-tv-viewing.html

Papacharissi, Z., & de Fatima Oliveira, M. (2008). News frames terrorism: A comparative analysis of frames employed in terrorism coverage in U.S. and U.K. newspapers. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(1), 52-74.

Papacharissi, Z., & de Fatima Oliveira, M. (2012). Affective news and networked publics: The rhythms of news storytelling on #Egypt. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 266-282.

Parker, A. (2012, January 28). In nonstop whirlwind of campaigns, Twitter is a critical tool. New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/29/us/politics/twitter-isa-critical-tool-in-republican-campaigns.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Patterson, T. E. (1993). Out of order. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Poell, T., & Borra, E. (2011). Twitter, YouTube, and Flickr as platforms of alternative journalism: The social media account of the 2010 Toronto G20 protests. Journalism, 13(8), 1-19.

Project for Excellence in Journalism (2007, October 29). The invisible primary—invisible no longer: A first look at coverage of the 2008 presidential campaign. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://www.journalism.org/files/legacy/The%20Early%20Campaign%20FINAL.pdf

Purcell, K., Rainie, L., Mitchell, A., Rosenstiel, T., & Olmstead, K. (2010, March 1). Understanding the participatory news consumer: How Internet and cell phone users have turned news into a social experience. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Understanding_the_Participatory_News_Consumer.pdf

Rainie, L., & Smith, A. (2012, September 4). Politics on social networking sites. Pew Research Center Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved December 11, 2014 from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_PoliticalLifeonSocialNetworkingSites.pdf

Reber, B. H., & Benoit, W. L. (2001). Presidential debate stories accentuate the negative. Newspaper Research Journal, 22(3), 30-43.

Sankaranarayanan, J., Samet, H., Teitler, B. E., Lieberman, M. D., & Sperling, J. (2009).

TwitterStand: News in tweets. Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, 42-51.

Schill, D., & Kirk, R. (2014). Issue debates in 140 characters: Online talk surrounding the 2012 debates. In J. A. Hendricks & D. Schill (Eds.), Presidential campaigning and social media: An analysis of the 2012 campaign (pp. 198-217). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sharp, A. (2012, October 4). Dispatch from the Denver debate. The Official Twitter Blog. Retrieved December 11, 2014, from https://blog.twitter.com/2012/dispatch-from-the-denver-debate

Smith, L. R., & Smith, K. D. (2012). Identity in Twitter’s hashtag culture: A sport-media-consumption case study. International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(4), 539-557.

Trussler, M., & Soroka, S. (2014). Consumer demand for cynical and negative news frames. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 360-379.

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. New York: Free Press.

Twitter reports third quarter 2014 results (2014, October 27). Retrieved December 11, 2014, from http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/AMDA-2F526X/3705477860x0x788942/56ff9307-8505-4fe99ca6-fb84aba86863/2014%20Q3%20Earnings%20Release.pdf

Yawn, M., Ellsworth, K., Beatty, B., & Kahn, K. F. (1998). How a presidential primary debate changed attitudes of audience members. Political Behavior, 20(2), 155-181.

Kyle Heim is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication and the Arts at Seton Hall University in South Orange, N.J., where he teaches courses in social media, communication research methods, journalism history, and media writing. His research, which has been published in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly and the Handbook of Mass Media Ethics, focuses on the influence of social media on journalistic practice and political communication. Heim was the recipient of a 2014-15 AEJMC/Scripps Howard Foundation Visiting Professor in Social Media Grant and spent two weeks during the summer of 2014 observing the Knoxville News Sentinel’s usage of social media in its daily operations. Heim has a Ph.D. in journalism from the University of Missouri and a master’s degree from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. Heim worked for 15 years in the news industry, including editing positions at the Chicago Tribune and the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

One thought on “Live tweeting a presidential primary debate”