Digital divisions: Organizational gatekeeping practices in the context of online news

Digital divisions: Organizational gatekeeping practices in the context of online news

By Joshua Scacco, Alexander L. Curry and Natalie J. Stroud

Digital technologies have changed the means by which media organizations produce the news. Using gatekeeping theory, current research has treated news organizations as relatively homogenous, as opposed to analyzing the differences that exist within and across newsrooms about how online news should be produced. This research uses gatekeeping theory to qualitatively examine the accounts of 21 online news personnel from 16 leading news organizations in the United States. The results reveal digital news divisions centered around two themes: resource constraints and news socialization practices. Both of these themes have components that are internal and external to news organizations.

Newsrooms have made extensive changes as they navigate the evolving journalism landscape. One theory implicated by these changes is gatekeeping, or the process by which all available information is narrowed down to the few pieces of information that make up the news (Shoemaker & Vos, 2008). Gatekeeping processes have evolved as the digital news product has gained importance. At the BBC, for instance, the arrival and incorporation of user-generated content has modified the venerable news outlet’s traditional gatekeeping role (Harrison, 2010). Users’ ability to personalize their news website experience has created a newsroom culture where gatekeeping functions are now shared (Thurman, 2011) and audiences perform a secondary gatekeeping role (Singer, 2014). Studies like these add valuable information to our understanding of the audience’s gatekeeping role. What is missing from this literature is a discussion of how the shifting landscape has led to digital divisions within and across news organizations. Our research seeks to fill this void.

With few exceptions, current gatekeeping research exploring how newsrooms are dealing with contemporary challenges has treated news organizations as a relatively homogenous group (Cook, 2006), as opposed to analyzing differences of opinion that exist, particularly regarding how online news should be created, packaged, and distributed. This omission is relevant because different opinions within the newsroom affect the external news product. We argue, and the data in this paper support, that online news has divided how news organizations approach resource allocation and socialization. Divergences exist within newsrooms as well as in how newsrooms seek to engage the public.

This research provides an explanation of digital news divisions within and across news organizations. To that end, we performed a qualitative analysis of data collected during two separate day-long interview sessions with groups of digital news leaders from the United States’ leading news organizations. Results reveal organizational gatekeepers who frequently are not of the same opinion on how to approach digital news and the ways in which these disagreements affect news organizations.

Organizations and Gatekeeping

Gatekeeping is the process whereby individuals make decisions about which ideas, products, and messages should be passed on to others. When applied to the news media, gatekeeping theory analyzes how the many available pieces of information are winnowed to the select group of items that make up the news (Shoemaker & Vos, 2008). The earliest formal research on gatekeeping, for instance, identified that the personal preferences of an editor affected which wire stories became news articles (White, 1950). In subsequent years, scholars have examined numerous gatekeeping influences on the news product—from the ideological characteristics of individual journalists (Patterson & Donsbach, 1996) to societal assumptions about what should be covered (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009).

To categorize the variety of gatekeeping influences, Shoemaker and her colleagues (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009; Shoemaker & Reese, 2014) developed a typology. Called the Hierarchical Influences Model, five levels of influence on which bits of information become news have been identified: individuals, routines, organizations, social institutions, and social systems. News organizations, despite their competition for audiences, share similar formal structures, including beats and organizational hierarchies, as well as informal structures like routines of source outreach and professional values that influence news production. These structures, routines, and values unite all news organizations in a much broader institution (Cook, 2005). Livingston and Bennett (2003), for instance, investigated reporter, organizational, economic, and technological influences on event-driven international news at CNN. They noted that despite a rise in event-driven international news, official sources still dominated stories—a testament to the influence of journalistic routines and values.

The transition to digital news has brought about changes in gatekeeping influences. To date, research has focused mainly on the routines and social institutions levels of influence. The routines level involves standard procedures and widely-held beliefs about how to make the news. Deadlines, for instance, can limit how much information journalists are able to obtain for a story. Digital news has changed news routines. Instead of preparing the news for a single publication or broadcast during a day, the internet era demands 24/7 news. News values also have shifted. Based on her ethnographic work at The New York Times, Usher (2014) argues that the transition to digital news has introduced values such as interactivity that affect the news product.

The social institutions level, which includes audiences and profit motivations, also has been influenced by the transition to digital. Audiences now play a role in the gatekeeping process by emailing news content to others, commenting in response to news stories, and submitting digital news content (Owen, 2013; Shoemaker & Vos, 2009; Singer, 2014). As a consequence, newsrooms must negotiate for control over the observation, selection, and filtering stages of news production (Hermida et al., 2011). Efforts at controlling citizen influence have the effect of digitally re-instilling a newsroom gatekeeping role (see Boczkowski, 2004; Deuze, 2003; Domingo, 2008).

The profit motivation aspect of the social institutions level also has shifted with the transition to digital news. Organizational hierarchies traditionally separate journalistic from business interests, creating figurative and sometimes physical divides (Gans, 2004; Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2007). Digital news has heightened commercial pressures. News organizations are searching for new business models since digital revenues pale in comparison to traditional, ad-based revenue streams (Holcomb, 2014). Nguyen (2008) argues that economic viability concerns led legacy media to adopt emerging news technologies while being “restrained within a traditional value network” (p. 93). From a gatekeeping perspective, a focus on profit can push news organizations to make different editorial decisions.

The benefit of the hierarchy of influences model is that it can expose gaps in our understanding of what influences the news. Although the routines and social institution levels have been examined in light of the digital transition, the organizational level of influence has received comparatively less attention. The organizational level involves “management styles, goals, news policies, size, newsroom cultures, and staffing arrangements” that vary across news organizations (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009, p. 63). How the digital transition influences the production of the news requires more research.

Our work examines current gatekeeping at the organizational level of news, placing this study in the context of research on the sociology of news (Berkowitz, 1990; Cook, 2005; Gans, 2004; Robinson, 2007; Usher, 2014). This perspective looks at how intra-organizational influences shape the news produced. At legacy television and newspaper outlets, newsrooms traditionally are structured in a tiered manner where editors and producers serve as the gatekeepers for stories written by journalists (Cook, 2005). Hierarchies work to “minimize threats to that control and identity” (Bimber, Flanagin, & Stohl, 2012, p. 20). Berkowitz (1990), in his observation of a network-affiliated television station in Indianapolis, found that news decisions were largely group-based, with power tipping toward the news director. As a consequence, individuals—whether journalists who report to editors or news producers who report to executives—must be socialized to the mindset of superiors in order to successfully market stories (Cook, 2005). Hierarchies are a critical gatekeeper in this regard.

The rise of digital news directly challenges gatekeeping influences within news organizations. The transition to digital involved re-arranging newsrooms. As Shoemaker and Reese (2014) describe, some newsrooms created separate digital and print divisions. As news organizations restructured and sought to integrate digital technologies, new goals and purposes emerged for digital news stories, including a greater flexibility to “breakaway from formulaic storytelling” (Robinson, 2007, p. 311).

Much contemporary scholarship has focused on commonalities in how traditional organizations approach online news. Scholars have looked for cross-organization patterns in how journalists think about their roles (Cassidy, 2006; Singer, 2006), how news is presented online (Singer, 2014), and gatekeeping divisions between journalists and the audience (Bro & Wallberg, 2014; Harrison, 2010; Lee, Lewis, & Powers, 2014; McKenzie, Lowrey, Hays, Chung, & Woo, 2011; Tandoc, 2014; Thurman, 2011; Vu, 2013). Cassidy (2006), for example, found that print and online journalists’ conceptions of professional roles were influenced similarly by sources, training, bosses, and economics. Although many of the studies were sensitive to differences across various news organizations, the research conclusions looked at patterns across organizations. What is lacking in this wealth of scholarly findings, however, is the story about the gatekeeping divisions that exist within and across news organizations.

With limited exceptions (e.g., Anderson, 2011; Robinson, 2007), recent scholarly efforts have treated journalists as a homogenous entity. Although conceiving of journalists in such a way may be helpful for explicating the divisions that exist between the audience and journalists, doing so fails to highlight the uniqueness of journalists and the organizations in which they operate. Indeed, Cook (2006) warned of this when he stated: “I fear the homogeneity hypothesis is too often treated as a matter of faith rather than a starting point for empirical analysis” (p. 164). The state of affairs for one organization may not be the same for others in the digital news environment, precisely as the organization level of the gatekeeping model suggests. To really understand the impact that audience interaction, emergent media, and other innovations have on newsrooms, it is vital to examine the digital divides that may exist within and across newsrooms.

To be clear, several recent studies have peered into newsrooms (Robinson, 2007; Singer, 2004; Usher, 2014; Vu, 2013), but none with the particular focus that we undertake here. Anderson’s (2011) ethnography illuminated how three different newsrooms navigated their journalist/audience relationships. Although Anderson highlighted some tensions between reporters and other newsroom staff related to audience interaction, the thrust of his research was not internal newsroom divisions, so much as the tensions between newsrooms and their audiences. McKenzie et al. (2011) looked at differences in how journalists focused on audiences based on factors that included community and news organization size, but did not explore differences in organizational culture. Tandoc (2014) reported on the ways in which audience interaction and the availability of audience metrics influenced newsroom practices. Although his study shined a light on newsroom activities, his arguments were based on the “balancing act” between universal journalistic values and a new ability to tailor the news product to the audience (p. 12). Singer (2004) analyzed how print journalists navigate converged newsrooms, where print co-exists with other media forms such as digital news production. Consistent with our analysis, she uncovered some tensions within newsrooms. Our work extends her findings by looking at impressions of internal divides by digital news leaders, as opposed to print journalists, and by considering variability across different newsrooms.

We suggest that looking at divisions in organizational gatekeeping practices within and across newsrooms will be of scholarly worth in helping to explain the current state of online news gatekeeping. This conclusion was reached not only because it was the major theme that emerged from our extended interviews, but also because of the many gatekeeping issues over which newsrooms are and can be divided.

Method

Data were collected from two separate day-long in-depth interviews with groups of digital news representatives. The first session was held in February of 2014 and was attended by representatives from 10 news organizations. The organizations were: CNN, Daily Beast, National Public Radio (NPR), The Arizona Republic, The Dallas Morning News, The New York Times, The Sacramento Bee, The Texas Tribune, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post. Attendees from these news organizations held various senior level, digital news-related positions within their organizations, such as Chief Digital Officer and Chief Innovation Officer.

The second set of interviews were conducted in November of 2014. Again, participants came as representatives of 10 news organizations, and although some of the same organizations were represented at both interviewing sessions, none of the individuals participating in the first session participated in the second one. The organizations were: CNN, The Denver Post, Gannett Digital, NJ Advance Media, NPR, Philly.com, Politico, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and Vox. The job titles of those attending included Director of Digital Products, Vice President, Digital Outreach, and other senior-level positions.

Data Collection

Each in-depth interviewing session took place over two days, and activities were comprised of moderated roundtable discussions, small group brainstorming sessions, and short (roughly 10 minutes in length) individual presentations by each participant. Both sessions were audio recorded, producing a total of 20 hours of recordings.

At both sessions, the moderator posed questions to the participants related to their responsibilities and opinions about digital news. The following are typical questions asked of the digital news representatives: What constitutes success in digital news innovation? What role should news audiences have? Are fragmentation and personalization problems or opportunities? What could your organization do to address polarization? What opportunities and challenges are there in today’s digital news environment? To facilitate discussion among participants, follow-up questions were used in the moderated portions of the sessions. Responses to these questions formed the backbone of the major discussion topics that emerged.

Data Analysis

The authors independently and collectively analyzed the audio recordings as well as the notes they took during the sessions, looking for patterns and themes in the participants’ comments. Suggestions abound for how to conduct qualitative data analysis, especially related to ensuring a study’s rigor and trustworthiness (Adcock & Collier, 2001). For our purposes, we followed an emerging pattern design, where pattern discovery was informed by the organizational gatekeeping theoretical framework outlined in our literature review. Although we did not pursue a grounded theory methodology, we were nevertheless guided by Lincoln and Guba (1985), as well as Shenton (2004), in utilizing several techniques to help ensure the credibility of our analysis. Specifically, we used member checks, a growing familiarity with journalistic culture, internal rounds of reflective commentary, and comparisons among interviews sessions to substantiate our results and subsequent conclusions.

Results

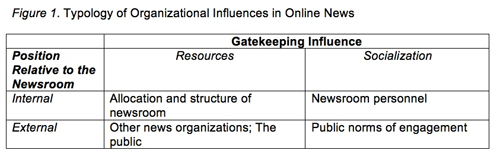

From an organizational perspective, we identified two themes mentioned by the digital news professionals as key gatekeeping influences: resources and socialization. Each was discussed with respect to considerations internal to the newsroom and considerations external to the newsroom, such as the role of the public.

As Figure 1 illustrates, digital news professionals face a central challenge at the organizational level of gatekeeping. Digital news makes news organizations both inward and outward facing to varying degrees. Newsroom personnel must look inward at their own practices of resource allocation and staff socialization while outwardly seeking to integrate the public and shape engagement norms as part of the gatekeeping process. The accounts we analyzed illustrate rich divergences on how news organizations are navigating organizational gatekeeping internally and externally around resources and socialization.

Resources

A common refrain among participants was that finite resources limited their abilities to meet the challenges facing digital newsrooms. Participants described both internal and external resources. Internal resources include a news organization’s financial assets, staff size and talent, time, and data tools. External resources involve assets that exist outside the newsroom, such as the organization’s unique news audience or their ability to monitor and follow the lead of competitors. As we discuss below, resources affect the gatekeeping process.

Internal resources. Internal resource availability provides the most immediate constraint under which news organizations operate. Finances act as a critical gatekeeper within newsrooms, as the amount and allocation of funds dictate the availability of other resources, most especially staff (which has both size and talent components). Staff size and talent then play a role in how newsrooms are able to spend their time, as well as what they are able to do with any audience data they collect. It was not uncommon to hear participants talk about ideas and practices as tied to a financial outcome. For example, one participant wanted to:

(assign) a cost value to every piece of content that we produce that says this is how much it cost in terms of a fraction of salary for the guy who wrote it, his gas money, and comparing it against the ads we had on the page, what the click-throughs were, what the impressions were for that page, and the whole chain cycle.

One breakout group echoed this statement, nominating return on investment (ROI) as a new metric. They wanted to know how much effort the outlet, editor, and writer were putting in to producing a piece of journalism compared to the outcome of the effort. Reliance on ROI measurements could have a profound influence on what becomes news in a gatekeeping process.

Financial constraints provided the explicit or implicit undertones to much of the discussion surrounding resources. One participant noted: “We are a very slim team, as I think everybody [here at the interview session] is, and we can’t really afford to not be focused.” With a similar focus on financial constraints, another participant said: “We have to ask whether we’re going to be the best at seven things, or just okay at 25 things.”

Some newsrooms felt that resource constraints limited their organization’s digital capabilities. For example, as participants discussed the use of A/B testing on their websites, one participant from a national news outlet expressed amazement at how much experimentation was occurring at several of the other organizations, exclaiming: “Where do you get the resources?!” This participant, like many others, expressed not only surprise at how others had overcome limited resources, but also disappointment that their organization was not innovating in similar ways.

As evidenced in the previous example, news organizations are not hamstrung by limited resources—most are developing innovative offerings and techniques in their newsrooms. One participant created an analytics team to help reporters improve how they wrote and packaged online content. Another not only created innovation teams, but also produced new digital products meant to improve the audience experience. Another participant stated that, “a social team and a homepage team are in place to examine the headlines that work… [and] an in-house platform was built for social sharing.” Other participants were able to leverage resources to create unique audience-focused products, including unique polling structures, commenting platforms, and even virtual reality immersion experiences.

One topic that was discussed in relation to resource issues was the online comment section. In wrestling with how to create a good commenting atmosphere, participants agreed that resources were a requirement. Some organizations invested immense resources; as one participant reported, “We use active moderation. Although it is vastly resource intensive, having a human make a space where readers are encouraged to contribute meaningful comments makes the comments more readable for other people.” Another said, “We had editors going through and pointing out the ‘comment of the day,’ and that got a lot of really good response.” Others faced constraints in dedicating staff time to commenting. One participant stated: “It would be great if every reporter could be in the comments after [they finish their story], but that’s not realistic.” Another noted: “Partially for resource reasons, partially because it’s political, we didn’t want to get in the fray too much.” One participant, noting how his organization had followed the lead of another, indicated: “The Washington Post was highlighting comments, which I thought was interesting. We tried that for a while, but unfortunately, we downsized.” Other participants echoed the sentiment that resource constraints limited their ability to build a more ideal commenting environment.

Although digital metrics (e.g. number of page views, unique site visitors, social media article sharing, etc.) are consistently logged, many newsrooms lacked the resources to understand the complicated array of numbers generated on a real-time basis. As one participant noted, “there is little sophistication in how metrics are examined.” Another summed this up when he said: “We spend a lot of time depending on our numbers and our measurements, and I’m convinced that we’re not really always right about a lot of it.” Even when the data are gathered, the numbers do not always provide newsrooms with meaningful details about site visitors. Expressing a wish for more substantive data, one participant stated:

We talk a lot about … capturing … data, but we don’t know who [the visitors really are]…. We know the people that are coming once a month or once a year, and we have some sense of why…. But what we’re trying to do now—and I think it is the next frontier—is to put a face on that and learn a lot more.

Although technology will inevitably catch up to the point that such information will be available to newsrooms, how news organizations use data will still be constrained by other available resources.

In sum, internal resources affect gatekeeping within organizations. How staff and monetary resources are allocated affects whether comments are moderated, whether data are mined for insights on news presentation, and how digital innovation is pursued.

External resources. News organizations also look beyond their walls for resources that will help them improve their reporting and their bottom line. Specifically, they take cues from other organizations and from their audience.

To find ways to advance their newsroom culture and to build new products, some organizations are looking to the examples of others. One participant worked on an innovative polling tool. The participant stated: “We worked with a graphics team to do that, but I think the real key to this—and this is what we learned from competing with The New York Times—is that if you’re going to spend the energy in doing this, you have to templatize it at the end of it, because otherwise, you really just wasted a lot of time for a story that lasted five days.” Although learning from competitors is nothing new, some specifically referenced the willingness of others to share digital insights. When one news organization wanted to build a custom analytics program, they “went and talked to a bunch of people: The New York Times, BuzzFeed, The Atlantic….” Indeed, this collaborative mentality was in evidence throughout the workshops.

Another external resource mentioned by the news representatives was audience engagement. Leveraging the audience as a resource emerged when the participants described involving the audience in the news-creation process. Several talked about using loyal audience members to moderate a comment section or write pieces for the news site: “One of the things I hope we could do in the future is find a way for readers … to help moderate. We also had … select members of the community post blog posts.” Figuring out how to maximize the business returns of audience engagement also emerged as a central point. One participant said:

I’m not remotely convinced that commenting is the right way to get people to interact. I’m willing to say that the majority of us would say that the majority of comments on stories have no civic value, and commenting overall has no business value. So the question is, what do you replace it with?

Overall, the availability and allocation of internal and external resources constrain news organizations’ abilities to pursue many worthwhile endeavors. The diverse resource constraints facing the organizations interviewed for this study affect what becomes news and what is presented to audiences online.

Socialization

The second emerging theme revolves around how newsroom personnel are socialized to operate within both the confines of limited resources and the expansive digital news landscape. The emergence of innovative forms of news production and dissemination has summoned critical needs associated with socialization. Internally, news personnel highlighted the immediate need to learn and adapt to an influx of real-time data as well as emerging forms of news writing, re-packaging, and dissemination. Externally, news gatekeepers faced the question of how best to engage the public as citizen-based news producers, disseminators, and commenters alongside the news outlet.

Internal socialization. Becoming effective members of a news outlet requires personnel to learn the structures, management styles, and values of an organization. Newsroom gatekeepers approach the socialization process differently when it comes to learning data metrics and emerging forms of news production. Although news organizations understand and are attempting to expand the training and role requirements of journalists, editors are simultaneously facing the challenges of adopting digital responsibilities.

The well-publicized conception of modern journalism is that user data has inundated newsrooms. A number of digital news personnel conceded that data-driven journalism is still in its infancy; “The newsroom is just starting to grapple with what it means to … bring analytics in a transparent way into the newsroom,” noted one participant from a major print-based outlet. User data “is all over the place, and we don’t have that one thing to tie it together;” further, it often needs to be processed before analysis. Participants saw a need for journalists and editors to better understand the analytics displayed on different data dashboards (i.e. Chartbeat, Parse.ly, Omniture, Visual Revenue, Hootsuite, and Facebook). This socialization can include “training print people to be digitally-minded” or re-training online news personnel on the latest data.

To confront the challenge of training and re-training personnel, some news organization representatives described using existing resources and organizational structures. For a number of media organizations, what an individual learns about online news data depends on where the individual works in the newsroom. One participant noted, “Our [dashboards are] broken down by teams. Everybody’s looking for different numbers for different reasons.” Other outlets similarly compartmentalized data knowledge, choosing to have “a data team who works with larger numbers” or a “data analytics guy” responsible for briefing journalists and editors. Within each of these teams, individuals are socialized as to what to look for in the data, such as click-through or video completion rates. Although potentially necessary based on the size and scale of the news organization, intra-organizational divisions may create data divides in the knowledge gleaned from audiences as a consequence.

Although some news organizations reported using a division of labor process that compartmentalized data analysis, several other representatives—particularly from digital-based outlets—embraced a flatter organizational design. “One of the things we’ve focused on in the past year is making all the denominators the same regardless of which part of the company you are in. Where we arrived at is the VPV—the value per visitor.” Another participant remarked that their organization was doing Google analytics primers in order to “get people conversant.”

Stark differences in data training emerged in one session. A participant from a smaller, digital outlet noted that the organization meets with staff individually to discuss their metrics, a means of training and familiarizing individuals with aspects of digital data. “We give them access to their author dashboard … So what we do every month is sit together with each of them … we’re a fairly small newsroom.” This approach did not seem feasible for larger news organizations, with one participant remarking that a small newsroom gives “a lot of flexibility.” The exchange revealed how organizational structures, size, and scale serve as critical gatekeepers in how individuals are socialized to interpreting news data.

The influx of user-generated data into the newsroom has tested gatekeepers’ conceptions of news writing, packaging, and distribution. Along a continuum, organizations vary in how they have responded to the reorientation necessary for online news production. Some digital staff recognized the resistance they faced from traditionally-minded individuals wedded to legacy-based writing techniques. One participant explained, “[Copy editors] tend to be the most traditionally-minded and I often think that if we … had a three-day seminar with all the copy editors and changed all of their minds at once, we’d be golden.” Intra-organizational debates occurred regarding not only what constitutes the news, but also how to write the news. “We have people who … don’t want to jump on the next trend,” noted one participant who then argued that the “news” no longer consists of only what the journalists thinks is important. “You can’t just … write about biking to work because you’re passionate about it.” These sentiments about news writing and production were echoed by other individuals who recognized a need to re-socialize individuals to the demands of online news writing. “We know that headlines matter. To respond, you have to reorganize in a way that is not always comfortable or in a way in which print has not deployed in the past….” Several of our participants remarked that online news still faces intra-organizational resistance in some quarters.

Digital news professionals discussed the challenges of socializing individuals to online news writing due to organizational structures and traditions. Although some organizations faced less resistance to re-tooling news for digital presentation, others faced structural limitations. One participant described “a legacy/print mindset” where “projects sometimes have to be tied to a print story to get first class treatment.” The participant, nonetheless, reported that more traditional individuals were re-learning approaches to news packaging. Digital divisions of labor also are quite different across news outlets. One participant noted that at their organization, “the division of labor [translates into different roles] … I’m the headline king, I’m the SEO king, I am the social graphic king.” The participant explained that individuals unaccustomed to particular divisions of labor must be (re)taught the practices and norms of organization-specific approaches to digital news production. Several professionals conceded that to meet their goals, they had to “[reorganize] in the way we deploy meaning” by trying new techniques like teasing stories at different times to determine what topics “get maximum eyeballs.”

At the other end of the continuum, online news professionals publicly reported little resistance to training individuals in digital news writing and production. Indeed, one participant described how the newsroom familiarized personnel with 10 different styles of headlines to consider when writing as well as implemented a collaborative process with the managing editor to discuss headline appropriateness. “We do a lot with headlines as well. We expect our writers to write them, but we first also ask them to think about whether they should be writing an SEO headline or a social headline.” Another participant reported their organization’s philosophy by succinctly noting that “Data are bad for telling you what to write, phenomenal for telling you how to package content.” This digital news professional encouraged news personnel to “take the learnings from Upworthy and BuzzFeed and try to own them in a more hard news space.” Moreover, a number of participants reported on the organizational flexibility needed to A/B test headlines and news content. One participant explained that 50% of the headlines were tested because “the advertisers do it all the time.” The organization had deputized a Homepage Editor responsible for testing.

The socialization process varies widely across news organizations. News staff are socialized to think about audience data, digital products, and maximizing news products for social and SEO differently depending on their organization. This socialization process is an important part of the organizational influences on gatekeeping as familiarity with these audience metrics can affect how the news is conveyed to the public.

External socialization. Previous research has focused on the extent to which newsrooms must now navigate the role of the public in news production (Boczkowski, 2004; Deuze, 2003; Domingo, 2008; Hermida et al., 2011; Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). The conversations with digital news representatives revealed another form of engaging with the public: socializing the public to participate on the news outlet’s terms. The digital news professionals debated the efficacy of engaging in external socialization and reinstating a strong gatekeeper role over public involvement.

Several participants remarked that their roles increasingly involve community engagement and outreach. One outlet not only solicits story requests from the public, but then integrates the citizen(s) who requested the story in reporting. “We’re going to bring them along to be part of the story to do part of the reporting. So it’s a very personal kind of a thing.” By merging and highlighting the citizen and elite gatekeeping roles, a news outlet can model appropriate forms of citizen engagement while maintaining control over the news production process. Another newsroom added that efforts to “invite the community to help them with the reporting” involve learning how to ask for citizen involvement. “What they’ve learned is that when you say, ‘Be a journalist,’ people say, ‘Oh, wait. I don’t have the qualifications for that.’ But if you say, ‘Share your expertise,’ then they respond a lot differently.” Discussing online weather reporting, one participant described his outlet’s efforts to deputize citizen meteorologists. “We have events where we train people to collect weather data. We bring in a National Weather Service person. So we’re doing a community event of some kind.…” The data produced by the citizen meteorologists then informs the newsroom in a process that again merges citizen and elite gatekeeping roles.

Organizational approaches to community engagement diverged when discussion turned to online commenting. One perspective advanced was that it is not the job or the place of newsrooms to ensure civil and deliberative commenting on news sites. “I would tell reporters not to engage at all because you could never win,” was the sentiment expressed by one participant. Another digital news professional stated: “We experimented a little bit with columnists going in and responding to comments, and the commenters didn’t like it. They said, ‘You have a column, you’ve had your say already, this is our space. Get out of here.’” In these cases, the news outlet made little effort to guide and socialize citizens on how to respond to the news.

The other approach we identified took a more interventionist perspective towards socializing the public to the norms of commenting alongside the news. One participant described “a concerted effort to be very aggressive in trying to make the content underneath the comments reflect the journalism that we’re trying to present.” One outlet identified community and thought leaders to moderate comments and “participate in public discourse on the site.” As a participant explained, “once [news staff are] in there and post, we can say, ‘Hey, this is a troll-free zone. We’re going to try to keep the conversation on-topic, respectful and relevant.’ And generally in that space and time that the staff is in there, it ends up being a pretty good experience.” Another participant saw their organization’s role as guiding the public toward a fruitful commenting experience. “When we actually talk to commenters about their bad behavior, they usually apologize or calm down … it seems that personal interaction works really well.” Although these efforts can be resource-intensive, some outlets have adopted this pseudo-pedagogical approach as part of their online news philosophy.

These varying approaches to external socialization illustrate how online news staff are still adjusting to the influence of the public as a news gatekeeper. Efforts to engage and socialize the public around a set of news norms offer an important account of how some digital news professionals are attempting to reassert elite influence over engagement online. Much as prior scholars have observed, greater digital “handling” of the public instills the traditional journalist gatekeeping role (Boczkowski, 2004; Deuze, 2003; Domingo, 2008).

Discussion

Discussions among 21 digital news staff reveal several organizational influences on the digital news gatekeeping role. First, monetary, data, and audience-based resources can be deployed in ways that influence the news product. In the digital environment, news staff thought about the return-on-investment, A/B testing, and how audiences could be leveraged in the production of news. Second, new forms of socialization appeared, including educating newsroom employees about digital metrics and molding how audiences interact with the news product. Both resources and socialization affect the digital news product, as gatekeeping theory suggests (Shoemaker & Vos, 2008). Although we did not examine the news product, the news representatives participating in our research made it clear that they were shaping the news product as a result of their organizational practices, such as A/B testing and a reliance on audience metrics.

Theoretically, our analysis adds to the growing literature on how gatekeeping has been modified by the transition to digital news (e.g., Shoemaker & Vos, 2009; Singer, 2014). Our research identifies the gatekeeping influence associated with resources and socialization practices that have become critical organizational factors in the modern news era. Cook (2006) cautioned against assuming that similarities exist among news outlets. Our research identified numerous differences among outlets. Some had more resources for digital experimentation than others. Some worked to ensure that all news staff were habituated to dealing with metrics, while others did not. These inter-organizational differences are a hallmark of the organizational level of the hierarchy of influences model.

One task for future research is to explain what factors contribute to inter-organizational differences. Although we are not able to reach a definitive conclusion as to the origins of these differences given our methodological choices, we do point to several possibilities. First, organizational differences exist between digital-first organizations (e.g. Daily Beast, Politico, Texas Tribune, Vox) and more traditional news organizations (e.g., CNN, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal). For example, we noticed that much discussion of “return on investment” started with representatives from digital-first organizations. Further, representatives of more traditional news organizations seemed to place more emphasis on cultural divides between legacy and digital personnel. Second, organizational size, a factor flagged by Shoemaker and Vos (2008), likely affects the resource and socialization processes identified in this paper. Indeed, size was directly implicated when one participant described meeting with all employees to review their metrics and another participant noted that this would not be possible in a larger newsroom. Whether size, digital-first versus traditional, or some other organizational attribute most affects the news product remains an important starting point for future research. What our analysis is able to show is that considerable diversity exists across outlets and, as the news representatives in this study suggest, it affects what news makes it through the gates.

The possible factors explaining why organizational-level differences in resource allocation and socialization have emerged may not be best answered with the qualitative approach employed in this analysis. We share these possibilities while cognizant that qualitative findings lack generalizability. Our conclusions, sketched from the insights of 21 digital news professionals at 16 prominent news organizations, may not reflect the reality of other news organizations nor the factors underlying gatekeeping practices outside of our sample. That being the case, we are confident that our diverse sample, which is made up of news organizations representing national and local audiences, as well as print, broadcast, and digital-only news outlets, helps us flesh out a picture of struggles and change occurring in news organizations throughout the United States. Furthermore, our conclusions have been corroborated by member checks as well as subsequent visits with interview participants and additional newsrooms.

Conclusion

Digital news has created both challenges and opportunities for news organizations. Cross- and intra-organizationally, many news outlets are negotiating internal and external approaches to resource allocation and socialization as they focus increasingly on digital news. Accounts from digital news professionals suggest that many divergent approaches exist across newsrooms and implicate news gatekeeping. By engaging in extensive conversations with online news gatekeepers at digital and legacy organizations, we have uncovered evolving organizational news dynamics.

At the heart of the evolution of online news is the realization that a once similar outcome known as “the news” has fragmented, partly based on divergences in organizational gatekeeping. The rich perspectives of the personnel interviewed as part of this study present an important counterpoint to the homogeneity thesis. Resource allocation, both internal and external, is now approached quite differently. Newsroom structures and audience-based tactics are seemingly more tailored to the unique needs of each news outlet. Organizations, as a consequence, have developed different socializing philosophies built within the structures of available resources. The accounts offered here reflect the richness inherent in understanding intra- and cross-organizational differences.

Understanding emerging organizational dynamics may have critical implications for the subsequent content of online news. Gatekeeping theory would suggest that differences in organizational-level practices give greater variety to the perspectives, packaging, and dissemination of the news. Information provided to the public could be affected as a result. Although commercially-beneficial for news organizations, do “curiosity headlines” alter the frames of stories? Might individuals view the news differently based on the packaging of a story? The implications of digital news divides could be far-reaching.

The story of news gatekeeping often gets reduced to one of uniform influences on the news product: time constraints, newsroom structures, professional values, and more. A modern narrative integrates the push-pull between elite news and citizen gatekeepers. Although news organizations face similar gatekeeping forces, which unite disparate outlets in a broader institutional entity (Cook, 2005), digital news tests the foundations of this notion. The forces confronting news outlets may be similar, but organizational gatekeeping approaches to resource and socialization forces are diverging. This divergence is reshaping news organizations’ gatekeeping roles and what we know of as the news.

References

Adcock, R., & Collier, D. (2001). Measurement validity: A shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. American Political Science Review, 95(3), 529-546. doi:10.1017/ S0003055401003100

Anderson, C. (2011). Between creative and quantified audiences: Web metrics and changing patterns of newswork in local US newsrooms. Journalism, 12(5), 550–566. doi:10.1177/1464884911402451

Berkowitz, D. (1990). Refining the gatekeeping metaphor for local television news. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 34(1), 55-68. doi:10.1080/08838159009386725

Bimber, B., Flanagin, A. J., & Stohl, C. (2012). Collective action in organizations: Interaction and engagement in an era of technological change. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Boczkowski, P. J. (2004). The processes of adopting multimedia and interactivity in three online newsrooms. Journal of Communication, 54(2), 197-213. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02624.x

Bro, P., & Wallberg, F. (2014). Digital gatekeeping. Digital Journalism, 2(3), 446-454. doi:10.1080/21 670811.2014.895507

Cassidy, W. P. (2006). Gatekeeping similar for online, print journalists. Newspaper Research Journal, 27(2), 6-23.

Cook, T. E. (2005). Governing with the news: The news media as a political institution. (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Cook, T. E. (2006). The news media as a political institution: Looking backward and looking forward. Political Communication, 23(2), 159-171. doi:10.1080/10584600600629711

Deuze, M. (2003). The web and its journalisms: Considering the consequences of different types of news media online. New Media & Society, 5(2), 203-230. doi:10.1177/1461444803005002004

Domingo, D. (2008). Interactivity in the daily routines of online newsrooms: Dealing with an uncomfortable myth. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(3), 680-704. doi:10.1111/ j.1083-6101.2008.00415.x

Gans, H. J. (2004). Deciding what’s news: A study of CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Newsweek, and TIME. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Harrison, J. (2010). User-generated content and gatekeeping at the BBC hub. Journalism Studies, 11(2), 243–256. doi:10.1080/14616700903290593

Hermida, A., Domingo, D., Heinonen, A. A., Paulussen, S., Quandt, T., Reich, Z., Singer, J. B., & Vujnovic, M. (2011). The active recipient: Participatory journalism through the lens of the Dewey- Lippmann debate. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, Texas April 2011.

Holcomb, J. (2014). News revenue declines despite growth from new sources. The Pew Research Center. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/04/03/news-revenue-declines-despite-growth-from-new-sources/Digital divisions: Organizational gatekeeping practices in the context of online news 129

Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Lee, A. M., Lewis, S. C., & Powers, M. (2014). Audience clicks and news placement: A study of time-lagged influence in online journalism. Communication Research, 41(4), 505–530. doi:10.1177/0093650212467031

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Livingston, S., & Bennett, W. L. (2003). Gatekeeping, indexing, and live-event news: Is technology altering the construction of news? Political Communication, 20(4), 363-380. doi:10.1080/10584600390244121

McKenzie, C. T., Lowrey, W., Hays, H., Chung, J. Y., & Woo, C. W. (2011). Listening to news audiences: The impact of community structure and economic factors. Mass Communication and Society, 14(3), 375–395. doi:10.1080/15205436.2010.491934

Nguyen, A. (2008). Facing “the fabulous monster:” The traditional media’s fear-driven innovation culture in the development of online news. Journalism Studies, 9(1), 91-104. doi:10.1080/14616700701768147

Owen, D. (2013). “New media” and contemporary interpretations of freedom of the press. In T. E. Cook & R. G. Lawrence (Eds.), Freeing the presses: The First Amendment in action (rev.) (pp. 141- 160). Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

Patterson, T. E., & Donsbach, W. (1996). News decisions: Journalists as partisan actors. Political Communication, 13(4), 455-468. doi:10.1080/10584609.1996.9963131

Robinson, S. (2007). “Someone’s gotta be in control here:” The institutionalization of online news and the creation of a shared journalistic authority. Journalism Practice, 1(3), 305-321. doi:10.1080/17512780701504856

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63-75.

Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (2014). Mediating the message in the 21st century (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Shoemaker, P. J. & Vos, T. P. (2008). Media gatekeeping. In M. B. Salwen & D. W. Stacks (Eds.), An integrated approach to communication theory and research (2nd ed.) (pp. 75-89). New York, NY: Routledge.

Shoemaker, P. J., & Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. New York, NY: Routledge.

Singer, J. B. (2004). More than ink-stained wretches: The resocialization of print journalists in converged newsrooms. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 838-856. doi:10.1177/107769900408100408

Singer, J. B. (2006). Stepping back from the gate: Online newspaper editors and the co-production of content in campaign 2004. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(2), 265-280. doi:10.1177/107769900608300203

Singer, J. B. (2014). User-generated visibility: Secondary gatekeeping in a shared media space. New Media & Society, 16(1), 55-73. doi:10.1177/1461444813477833

Tandoc, E. C. (2014). Journalism is twerking? How web analytics is changing the process of gatekeeping. New Media & Society, 16(4), 559–575. doi:10.1177/1461444814530541

Thurman, N. (2011). Making ‘The Daily Me’: Technology, economics and habit in the mainstream assimilation of personalized news. Journalism, 12(4), 395–415. doi:10.1177/1464884910388228

Usher, N. (2014). Making news at the New York Times. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Vu, H. T. (2014). The online audience as gatekeeper: The influence of reader metrics on news editorial selection. Journalism, 15(8), 1094-1110. doi:10.1177/1464884913504259

White, D. M. (1950). The “gate keeper:” A case study in the selection of news. Journalism Quarterly, 27(3), 383–390.

Joshua M. Scacco is an Assistant Professor of Media Theory & Politics in the Brian Lamb School of Communication and Courtesy Faculty in the Department of Political Science at Purdue University. He also serves as a Research Associate with the Engaging News Project (ENP), which conducts innovative research to improve the commercial viability and democratic benefits of online news. He is interested broadly in the communicative role elites and organizations, including political leaders, journalists, and news outlets, play in American political life. Scacco’s research has appeared in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, New Media & Society, the International Journal of Press/Politics, and the Journal of Political Science Education.

Alexander L. Curry is a doctoral student in communication studies at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also a research associate at the Engaging News Project. Curry’s research focuses on political communication and online news, and he is particularly interested in sports and the role they play in America’s political landscape. His work has appeared in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication and the Journal of Public Relations Research. From 2005 to 2010, Curry served as a writer for Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Natalie (Talia) Jomini Stroud is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Studies and Assistant Director of Research at the Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at the University of Texas at Austin. Since 2012, Stroud has directed the grant-funded Engaging News Project (www.engagingnewsproject.org), which examines commercially-viable and democratically-beneficial ways of improving online news coverage. Her book, Niche News: The Politics of News Choice (Oxford University Press) received the International Communication Association’s Outstanding Book Award. Her research has appeared in Political Communication, Journal of Communication, Political Behavior, Public Opinion Quarterly, Journal of Computer- Mediated Communication, and the International Journal of Public Opinion Research.

The authors thank the Democracy Fund, Hewlett Foundation, and Rita Allen Foundation for funding this project and the news organization representatives for making this research possible as part of the Engaging News Project.

One thought on “Digital divisions: Organizational gatekeeping practices”