Getting my two cents worth in: Access, interaction, participation and social inclusion in online news commenting

Getting my two cents worth in: Access, interaction, participation and social inclusion in online news commenting

By Fiona Martin

(Fiona explains her research in this short video.)

Online news commenting is an economically and politically important form of participatory journalism, but it is less clear to what extent it is socially inclusive. Building on Nico Carpentier’s model for understanding media participation, this international comparative study uses data analytics and content analysis to investigate commenting access and interaction in the top news websites from the U.S., U.K. Australia and Denmark. It finds that only 55% of these sites host in-house, moderated, everyday news commenting. It also finds a gender imbalance in high engagement sites, where women make up at most 35%, and as low as 3%, of commenters.

Introduction

In the past decade online news commenting has been recognized as an important form of audience engagement, content development, cultural and political participation. The New York Times Innovation report (2014, p. 51) notes that digital native publications like the Huffington Post have built business models around commenting that provide insights into what their users think, read and share. Editorial decisions are being increasingly shaped by user input and social analytics (Viner, 2013). In media policy circles user-created content has been seen as a measure of digital citizenship, media diversity, and cultural innovation (Turner Hopkins, 2013).

However, commenting’s relationship to social inclusion and voice diversity needs more critical examination. Despite widespread social media use, internationally less than 20% of online news consumers said they commented on news websites. Twenty-five per cent or less commented about the news on social media (Newman & Levy, 2014, p. 73). There are also early indicators of a gender bias in news comment participation (Pierson, 2014) and information and communications researchers have also begun to question the accessibility of online news participation for those with disabilities (Hollier & Brown, 2014; Khan, Iqbal & Bawany, 2013).

Yet the broader inclusiveness of commenting systems remains largely assumed and unchallenged—perhaps because of the range of contributory technologies that the news media now offer, from branded social media channels and comments sections, to annotations, forums and special event chat (see Braun & Gillespie, 2011; Singer et al, 2011; World Editor’s Forum, 2013). In this respect Dan Gillmor’s (2004: xxiv) case that the news media need to develop journalism as a “conversation” has, a decade later, become a truism of contemporary news publishing, whether or not reporters actually respond to user remarks.

This paper explores how effectively a sample of the world’s top news media sites structure social inclusion in news commenting, and where they fall short. It investigates the opportunities for regular, habitual news commenting provided by the 40 most popular online news services in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and Denmark. It then presents a big data content analysis of in-house news commenting on those news sites with a stated interest in user engagement. This research is based on data captured over three months from 15 publications, including The New York Times, The Guardian and The Sydney Morning Herald, and examines interaction in terms of site scale, scope and distribution of commenting, as well as gender inclusion.

The paper first proposes a model for investigating the significance, forms and scope of media participation and its relationship to social inclusion, a notion key to social equity policy in the countries studied. It then argues for the study of in-house news commenting alongside social media participation. The research design, which includes computational data analytics, content and textual analysis sets out an integrated approach to examining accessibility and participation in high engagement commenting systems. This research suggests lower than expected levels of in-house commenting accessibility, marked differences in interaction and participation among international, national commercial and public service media and regional publishers and, worryingly, indicates very low engagement by commenters with female user names.

Media Participation and Social Inclusion

This research is part of a three-year Australia Research Council funded Discovery project, which aims to investigate the best practice conditions for hosting and moderating productive, inclusive commenting in global news media forums. This module assesses whether users can freely and habitually comment on generalist online news, and how participation is structured in these commenting systems.

While media participation has a long, rich history beyond the Internet (Griffin-Foley, 2004) journalism academics’ interest in the concept has centered on user-generated content or citizen journalism and the civic role of online news media (Barnes, 2013; Borger et al, 2013). Borger and her colleagues conclude that the bulk of this literature critiques industry struggles to encourage and facilitate participation, rather than examining how users experience it. Participatory studies, they note, also have a strong interest in analyzing democratic practices, but are largely disappointed by online journalism’s failure to live up to its radical political potential.

Rather than bemoaning the apparent low levels of news participation and blaming passive audiences or unresponsive journalists, this research takes a critical Internet studies interest in exploring the structural, social and cultural barriers to contribution. It aims to uncover commenting trends in different news media sectors or platforms that might highlight forms of exclusion. It also seeks to reveal factors common to participative systems that might constrain or enable public commenting on the news. In this it takes up Graham’s (2013) challenge to reconceive journalism’s civic role online, extending it to the hosting and facilitation of public commenting and debate. To understand why someone might comment on the news, we need to explore not only their motivations and psychology, but what type of opportunities they are offered and what problems they might encounter in taking them up.

In the 2000s media participation has been a topic of interest to policymakers across Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia and other Western countries. Social inclusion policies seek to ensure all citizens have access to the opportunities and services they need for full participation in so-called “information societies.” Digital citizenship research emphasizes the benefits of media interaction and content creation in civic engagement and problem-solving (Cammaerts & Carpentier, 2005). A European Commission report on e-inclusion included content production and personal expression in online political communication as two of its digital social inclusion measures (Bentivegna et al, 2010). Until recently Australia’s federal social inclusion agenda aimed to support cultural and linguistic media diversity (Australian Government, 2013) a factor regarded as critical for the country’s many migrant and refugee communities. Social inclusion has not been widely adopted in U.S. policy circles, although it is attracting research and political interest (Bintrim et al, 2014; U.S. Department of State, 2014). However the principles have been raised in debates about racism and sexism in online media coverage, for example following the Ferguson riots and #Gamergate.

Digital divide research has shown us online exclusion is partly a problem of access to speech rights, technology, and skills (Van Dijk, 2008) and partly a question of motivation. Recent media studies also suggest inclusive digital media strategies need to recognize potential participants, attend to how discussions could be better hosted and consider user obligations to listen and respond to others in a conversation (Ewart & Snowden, 2012; Penman & Turnbull, 2012). Graham (2014) asks how online journalists can better facilitate and respond to comments. Yet to some extent this participative media research, important as it is, pre-supposes that the material conditions for media participation are already in place.

In the meantime news media are debating whether to host comments or to respond to user interaction. Many news publications have suspended comments in response to racist and personal attacks (Hare, 2014; Trygg, 2012), or domination of threads by “fringe ranting and ill-informed, shrill bomb-throwing” (Newman, 2014, par 5). A survey of 104 newspaper organizations found that while 93% had enabled in house or social media hosted comments, staff from one-third of sites did not participate in the threads because of time constraints or objectivity concerns (World Editors Forum, 2013). Others felt commenting sections were users’ space.

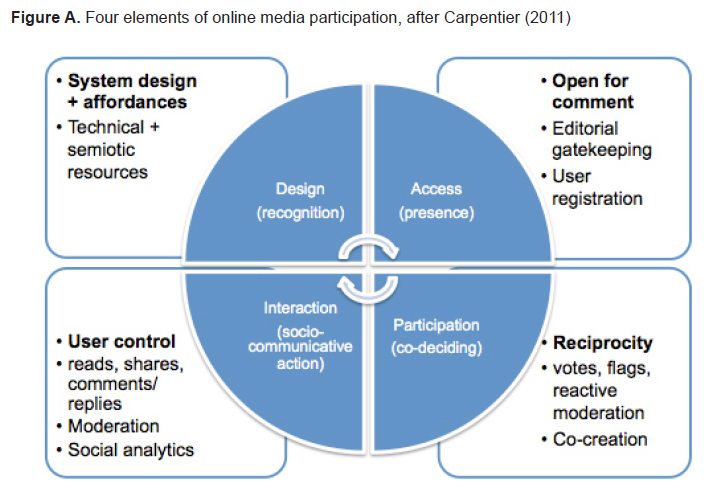

Carpentier (2011) proposes that most media interaction does not qualify as participation in the sense of offering users the chance to shape the system, their role in it, or the content that it produces. He argues that critical participatory analyses need to investigate models that enable richer forms of user co-creation and involvement in news production, without suggesting the symbolic annihilation of professional (elite) editorial roles. The object is, he says, to “transform these roles in order to allow for power-sharing between privileged and non-privileged (or elite and non-elite) actors” (2011, p. 26) and to diversify the societal identity of journalism “so that the processes and outcomes of media production do not remain the … territory of media professionals and media industries” (2011, p. 26).

In Carpentier’s model there are three aspects to media participation. Access to participative systems and interaction with documents or other users and journalists, are the “conditions of possibility” for participation (2011, p. 28) but have less political force. This is because users have little power to determine when they can contribute, and how their conversations and forms of co-creation with journalists are structured. They have less input into the everyday decision-making that shapes editorial and regulatory processes. Full participation however involves forms of “co-deciding” on the reporting and publication of content or the governance of interaction and so shapes media systems.

In this study access involves establishing a presence on commenting platforms—having the capacity to register to comment and to find comments sections. Interaction includes all forms of human/system activity and social relations. Co-decisive participation is illustrated where commenters can rank comments, flag abuse or errors, decide which contributions will be incorporated into stories, or help develop and apply moderation policy.

Carpentier’s model overlooks one key aspect to participation—system design. As Weber (2013) notes, online news services can delimit discursive participation simply by positioning content in the first visible region of a webpage, or “above the fold.” Inclusive interaction design recognizes diverse users as potential participants (for example, using text rather than image icons in signalling when comments are enabled on stories) and responds to changes in social relations (Martin, 2012). Thus recognition is another condition of possibility for news commenting. Figure A. sets out this expanded version of Carpentier’s media participation model.

Following Carey’s (1989) ritual view of communications, if news services want to increase inclusion in participation they need to design systems that embed opportunities for access, interaction and content co-creation into users’ everyday experiences of news, and produce shared communicative styles, signs and standards for commenting systems. Regular engagement with news commenting supports the enactment of assumed social roles and the building of ties between regular contributors, moderators and even (though rarely) journalists. It also cements brand loyalty, measured in return visits, time on site and other engagement indices (World Editors Forum, 2013).

Social media commenting and news sharing have assumed prominence in recent online news research (see Hampton et al, 2014) but this study focuses on in-house commenting due to its possibilities for more effectively governed, pseudonymous interaction. Social media may seem a low cost, low barrier, high control option for commenting users are exposed to unmoderated, unexpected hostility, abuse and provocation, establishing a cognitive barrier to participation—particularly for women, who are subject to “more bullying, abuse, hateful language and threats than men when online” (Bartlett et al., 2014, p. 3). Social media platforms are hard for publishers to govern as comments can only be post-moderated, dashboards offer few governance options and user accounts cannot be easily verified.

Social media users can also be deterred from speaking freely by privacy concerns and peer pressure. A Pew Internet survey of U.S. adults found that social media in the main did not provide alternative channels for discussion of the Snowden-NSA revelations (Hampton et al., 2014). People were unwilling to post to Facebook or Twitter about the issue, less willing to post on it than to discuss it face to face, and less willing to share their opinions online if they thought their social network might disagree with them, entering a “spiral of silence.” This reticence is not surprising given corporate monitoring of employees’ (and potential employees’) social media accounts.

So social media provide users naive inclusivity, accessibility without governability, interaction and visibility at the price of ongoing surveillance. They are a complement to, rather than a substitute for, professionally mediated commenting.

Research Design

Based on the media participation schema discussed above, this study involved three stages:

1. A platform access study of regular commenting opportunities in the most trafficked news media sites in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Denmark.

2. A big data analysis of the scale and scope of interaction in engagement-focused news sites.

3. Content analysis of gendered user names based on the top 100 commenter data from Stage 2, to explore participation bias.

The study originally sought to examine commenting in the top 40 most trafficked news sites in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Denmark. The United States and United Kingdom are diverse markets with globally important brands such as Huffington Post and Daily Mail that invite international, cross-cultural interaction. U.S. media companies have also played a significant role in online publishing and software innovation. The U.K.’s BBC and The Guardian have been leaders in developing public service oriented participatory systems. In contrast Denmark and Australia are small, highly concentrated markets, where online media tend to adapt, rather than innovate, participatory technologies. Denmark, a politically liberal country, has a surprisingly closed participatory news landscape with a growing dependence on Facebook interaction, while Australia has comparatively diverse, open participatory news environments, supporting a more geographically dispersed national population. As of early 2015, Australia has at least four new independent, daily generalist online news publications, all launched in the past decade: Crikey, New Matilda, The New Daily and Independent Australia. Denmark’s online news services were all based on legacy publications.

For this first section of the study, a list of the top 10 online news services in each country (n=40) was assembled based on publicly available audience metrics from reliable measurement sources, including Comscore, Nielsen, eBiz/MBA, Quantcast and Danske Medie Research. The sample was compiled first in November 2013 and then revised in late July 2014. The homepage and several news stories were scanned for evidence of news comment sections, forums, news blogs and social media channel promotion.

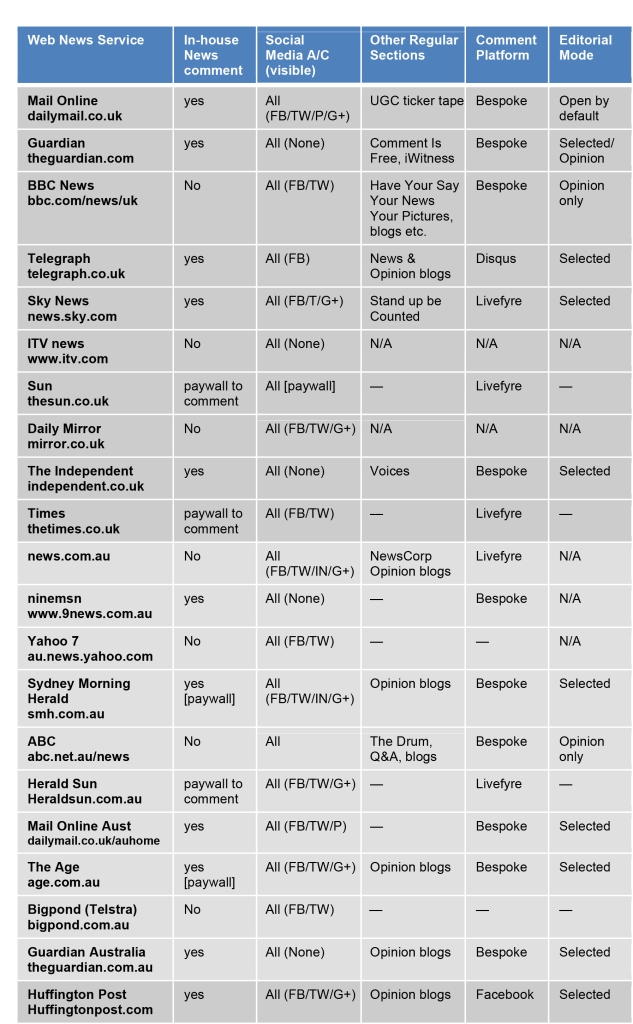

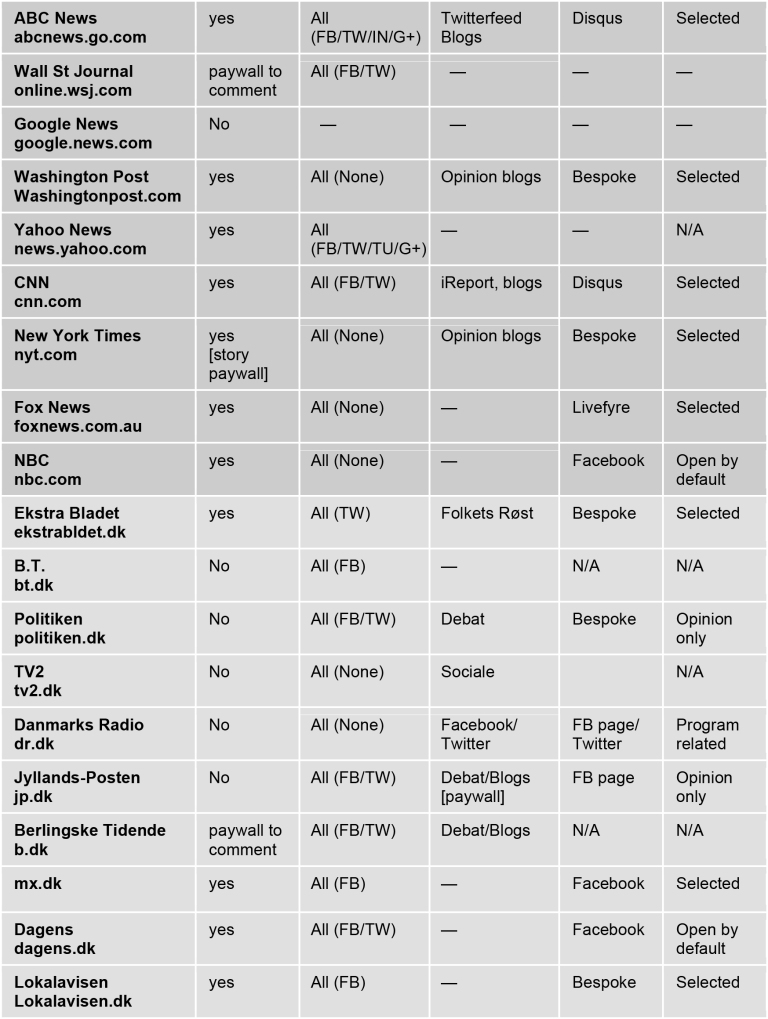

The social media channels promoted on the homepage were noted, for an indication of primary interactive focus. Commenting systems were examined for paywalls, third-party branding, or other evidence of services using turnkey management platforms such as Facebook plug-ins. The results of the study can be seen in Table 1. The services are not presented in order of traffic ranking due the difficulty of reconciling different audience metrics and the tendency of ratings to vary slightly from month to month.

The second part of the study involved a big data study of commenting scale and scope. This examined a smaller sample of websites, five from each of three countries, which had a stated interest in best practice engagement and nominations for online news excellence and innovation awards (Online Journalism Award, British Journalism Awards, Walkley Awards, Webbys). The sample included one newspaper, one broadcast organization and one digital native publisher in each country group in order to capture medium specific and platform related differences. A mix of international, metropolitan and local/rural publications was included in each country group. Finally an attempt was made to examine sectoral differences, with the inclusion of commercial and public service sites. The Stage 2 group included seven publications from the initial set, and eight new titles.

The publications analyzed were: in the United States, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Huffington Post, Texas Tribune, Orange County Register, PBS (Newshour); in the United Kingdom The Guardian, Daily Mail, Have Your Say (British Broadcasting Corporation, BBC), Liverpool Echo and The Conversation; in Australia, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Drum (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, ABC), The Conversation, the Illawarra Mercury and the Northern Territory News.

Some anomalies occur due to an absence of directly comparative news sources. In the United Kingdom where legacy news dominates the media landscape, it was not possible to find a digital native generalist news provider. The Conversation, an Australian non-profit publishing academic news features, analysis and opinion, which now has a U.K. edition, was substituted. In the United States, the Orange County Register was also added to provide a Facebook real-name commenting system comparison. In Australia, where two publishers control nearly 90% of the daily print news market, News Corporation’s Northern Territory News was added to examine participation in a hybrid local/metropolitan site. The Danish sites were not included due to the low number of sites enabling in-house commenting on news stories, lack of independent verification of best practice engagement and technical difficulties in capturing content for the data analytics stage.

The findings are necessarily qualified given the small sample from each country, but are indicative of trends that require further research given the internationalization of online news. The number of locally franchised, international brands in the sample (Mail Online, Guardian, Conversation), the tendency for online news users to consume titles outside their geographic market, and differences in country demographics made national comparisons questionable and so these are not represented.

The data analytics approach used produced a machine-readable corpus of comments, alongside full story data and thread metadata. The data was scraped from the homepages, or identified subpages of each news service, and where necessary sourced from paginated comments archives. The software running the scripts was WebHarvest v2, an open source Java-based application using processors that will accept HTML or JSON data and return valid XML. As the websites had idiosyncratic information architectures, customized scraping scripts had to be developed and run for each site. The processors first captured the story URL. Then three days after publication the story content and comments were harvested into a standard XML structure. WebHarvest, in combination with Chrontab (the ubiquitous Linux command scheduling tool), enabled batch execution of harvesting scripts. The data was captured from June 16 to October 5 2014.

There are always caveats to data analytics exercises of this scale and possibilities the regularity of the dataset may have been comprised during the collection period by unobservable changes to editorial practices, workflow, the interface or the back end systems supporting these news services. However the resulting corpus, which includes over 9 million comments, provides a robust representative sample of news participation. A sample of the collated data is available as a hyperlinked archive, with the files downloadable here: https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B2Rx_VeaU7ZTXy1halc3dW9JSTg&usp=sharing

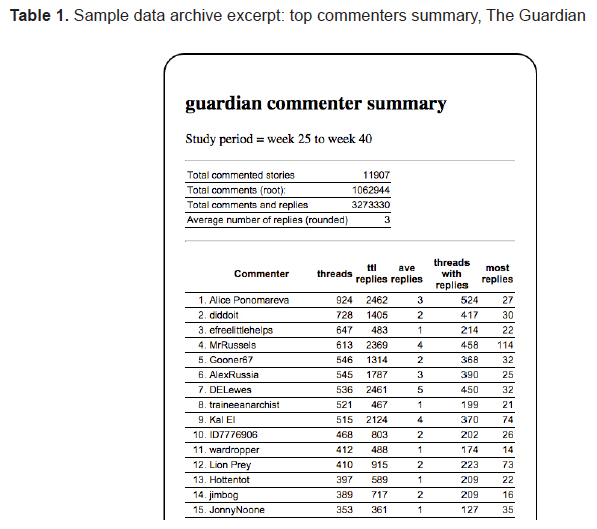

Commenting participation was then calculated, tabulated and graphed in terms of scale of commenting, number of commenters and stories opened for comment. Lists of the top 100 commenters were generated, with evaluation of their total original posts (root comments), no of replies generated, average number of replies and most commented stories, as shown in Table 1 below.

The final step was to examine the commenter summaries for evidence of social inclusion markers. Due to resource constraints, platform differences and variable user identification standards it was not possible to conduct a comparison of user profile demographics. Many commenters adopted pseudonyms and most did not create searchable profiles. Some may provide false information. However, the top 100 commenter summaries did provide user names, which suggested gender identities.

The top 100 commenter lists were then manually coded for gender orientation. Users’ first names were coded male, female or ambiguous/pseudonymous. Usernames that were gender neutral such as Chris or Elliot were counted as ambiguous. Usernames that included male gender references: Mr, man, boy, lad, guy, uncle and brother were coded male, as were obviously male pseudonyms such as Randy Old Codger and Alaric the Visigoth. Usernames that included female gender references: Mrs, gal, girl, lass, aunty and sister were coded female. Where possible, user profiles were cross-checked against gender identification, either self-reported or in images. An intercoder reliability check of 150 samples, 10 from each of the 15 lists, achieved 98.3% level of agreement.

There is a possibility that some female users have adopted male pseudonyms, in the George Eliot literary tradition. However, of the 15 sites, three have real-name Facebook commenting systems—Huffington Post, Orange County Register and Texas Tribune.

These provide a control to the sites that allow anonymous (guest) log-in or use of pseudonyms.

In summary, the methodology enables comparative assessment of material access in the top web news services for four countries. It then drills down into a comparative content analysis of commenter interaction in high engagement sites and gives insight into the gender inclusion patterns of their top commenters.

Access to News Commenting

Table 2 shows the extent of in-house and social media commenting opportunities across the sample of 40 top news websites in the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States and Denmark. It documents the provision of four key branded social media channels (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Google+), together with an indication of the visibility of the latter, or other channels (Pinterest, Tumbler) on the homepage. Other regularized opportunities for news-related commenting are noted in column four, while the final column records the commenting platform and the mode of opening stories for comment. The sample includes 20 legacy newspaper websites, 11 television broadcasters and nine digital native sites, a number of which are aggregation services and so package legacy news and news wire stories.

In-house commenting is, as expected, not as widely implemented as social media interaction channels. Only 55% of the online services examined hosted freely accessible, regular news comments sections. This figure rises to 67.5% when access to opinion and analysis commenting is included, although this does not always provide as immediate, predictable coverage of news events. Several companies had paywalls preventing or limiting comments, including four News Corporation sites The Sun, The Times, Herald Sun and The Wall Street Journal, which blocked access for non-subscribers. Berlingske.dk provided access to stories but required user subscription for commenting access. Others, such as The New York Times, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age employed a freemium model, which restricted content access but not commenting opportunities.

Legacy newspaper brands tend to lead broadcasters and digital natives in providing their own, moderated comments systems. Only of 54.5% of broadcasters offered in- house comments, although two of the public service broadcasters enabled commenting on news opinion. One-third of digital native sites did not enable comments, all of them aggregators.

Table 2. Comparative usage access in the top 40 web news services, U.K., Australia, U.S. & Denmark, July 2014

Table 2. Comparative usage access in the top 40 web news services, U.K., Australia, U.S. & Denmark, July 2014 (continued)

PBS Newshour was the only public service broadcaster to offer in-house commenting on news. The BBC and Australia’s ABC are under political and regulatory pressure to maintain news impartiality and have prioritized public sector expenditure on reporting rather than moderation costs. They opened a limited selection of opinion and analysis stories for comment in the BBC’s Have Your Say and ABC’s The Drum sections. Both channels also seek user news interaction in other ways though local station and current affairs websites, and innovative social broadcast hybrids such as the ABC’s Q&A program, which incorporates live moderated Twitter feeds. Danmarks Radio did not offer news commenting, but relied heavily on Facebook interaction. It even offered a page listing the many Facebook and Twitter channels it maintained for its various TV and Radio programmes: http://www.dr.dk/Service/socialemedier/. Relying on unfunded, private, third party channels like this is, however, a potential compromise to public sector independence and user privacy.

Without exception companies all maintained branded Facebook, Twitter, Google+ and Instagram accounts. Yet there were significant differences in how they promoted these on their homepages. More than a quarter of the sample including The Washington Post, The New York Times, BBC, The Guardian, ITV and The Independent did not push users to their branded social media from their homepages, although those links would usually be visible on story pages where the publication did not maintain in-house commenting. Facebook and Twitter links were often present on homepages, but less so Google+ or Instagram. Locating branded social media links was sometimes difficult, as the buttons or icons were located variously at the top of homepages, in right hand side columns amongst various forms of content and in the footer, or bottom information field, of pages. Icons were also displayed in various styles, sizes and colors. Thus finding these accounts might constitute a hurdle to access.

A key trend noted was the widespread use of integrated third-party platforms for managing commenting, including the Facebook plug-in, Livefyre and Disqus. While the majority of sites open for commenting had implemented bespoke in-house content management systems, all six News Corporation sites used Livefyre, four Facebook and three Disqus modules. In the data analytics sample discussed in the next section, three sites (Huffington Post, Orange Country Register and Texas Tribune) used Facebook and two (PBS Newshour and Illawarra Mercury) used Disqus to manage news comments.

Interaction in News Commenting

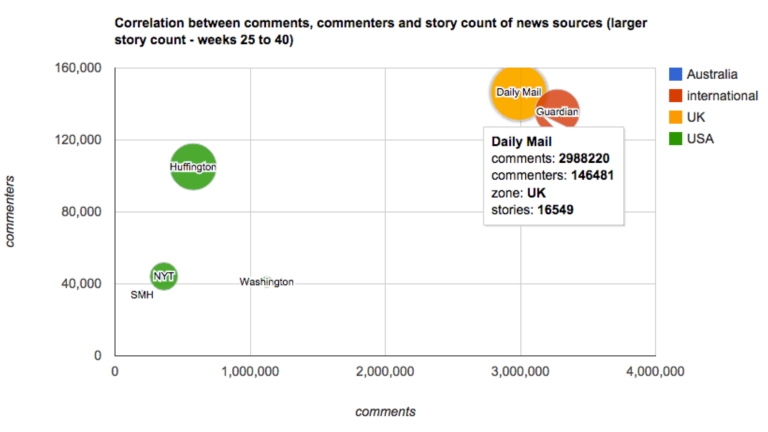

Figures B and C show the scope of interaction for each of the 15 sites by numbers of commenters, numbers of comments generated and the size of the bubbles, which represents the number of stories open for comment. The linked interactive version of the graphs also shows total numbers of comments, commenters and stories open for comment, as well a country zone. The Guardian and The Conversation, which comment count includes stories from United Kingdom and Australian editions, are coded as international sites.

In this graph The Guardian and the Daily Mail Online appear as the participation leaders, followed by the Huffington Post. These three publications have all adopted a deliberate high engagement strategy, with low barriers to participation and investment varies participative tools. The Mail Online introduced up and down votes on comments as early as 2009. The Guardian allows users to create individual profiles, which curate comments made, replies received, comments featured and content created. A digital native publication like Huffington Post employs 40 moderators and automated filters including JULIA, “just a linguistic algorithm” in order to quickly process user posts (Sonderman, 2012). What also distinguishes The Guardian and Mail Online, aside from the scope of their access opportunities, is the scale of participation, which draws on their local editions in the United Kingdom, Australia and United States.

There are correlations between the next three publishers—the metropolitan legacy broadsheet news services The Sydney Morning Herald, The Washington Post and The New York Times. All have subscription heavy revenue models and freemium paywalls. Here we can see the trade-off between engagement, quality and accountability, with each setting a threshold limit on the number of stories open for comment, in order to ensure the speed of moderation and civility of participation. The New York Times, for example, employs 14 full-time moderators, although it only opens 18 articles a day for comment.

Public service media and local publications sit at the other end of the news participation scale. Both the BBC’s and Australia’s ABC opinion commenting sites attract a high number of comments on relatively few stories. The degree of interaction is partly a reflection of their highly educated, loyal audience base, national and international reach, and editorial focus on encouraging debate on stories of wide social significance.

It was not a surprise to see PBS Newshour at the lower end of the scale with the regional publications, as the broadcast program has experienced a precipitous plunge in ratings over recent years. It was more interesting to see The Conversation in the lower range for both comments and commenters, given its international franchise. It is a relatively new enterprise though (launched March 2010) which doesn’t have the benefit of legacy branding or sustained audience development. It is also working with a pro-am journalism model and a cohort of academic writers trained in public commentary but not necessarily public interaction.

Early feedback on these findings suggested that it would be necessary to weight the figures and rankings by unique audience numbers or other measure of reach. However comparable audience metrics were not available for all publications and would not necessarily provide deeper statistical insights into relative usage access. This would be easier to gauge if we had access to other data on commenting accessibility for each news service, for example:

a. the proportion of all news stories open for comment (by genre)

b. the number of hours stories are open for comments

c. the period of the day stories remain open relative to changes in unique audience presence during the day.

Pursuing this data was far less important for this study than developing a better understanding of how inclusive these commenting environments are in terms of commenting distribution and demographics.

The Distribution of News Commenting

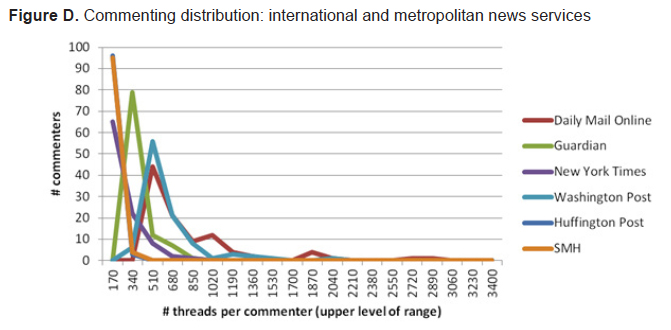

The scope of participation is suggested by the distribution of commenting amongst the top 100 commenters, which is illustrated in Figures D, E and F. As these graphs indicate, the distribution is remarkably similar across the three sectors and the majority of publications.

Figure F. Commenting distribution: local news services

The data from all 15 sites indicates that commenting occurs in what is known as a power law distribution with a long tail formation. There are a few highly regular contributors and a majority who only post on occasionally. A long tail occurs where a probability distribution shows a vastly larger share of a population occurring within one tail (in this case in the region of the lower frequency commenters), rather than evenly balanced either side of the mean as occurs under a normal distribution. Long tails in media have been observed following different statistical distributions. Chris Anderson (2006) envisioned the long tail of Internet sales as a power law distribution, while Brynjolfsson et al. (2010) found that the long-normal distribution provided a better predictor of Amazon book sales.

These distributions above illustrate the habitual practices of intense participants, central to the phenomenon editors describe disparagingly as the capture of comments sections by a small group of users, whose velocity of posting, consolidation of social ties and intimate address can work to exclude irregular commenters. The BBC’s tendency to a normal distribution deserves further analysis, to see whether it is a statistical anomaly or due to moderation techniques and posting constraints that ameliorate the domination of commenting by the very few.

Gendered Participation and Exclusion

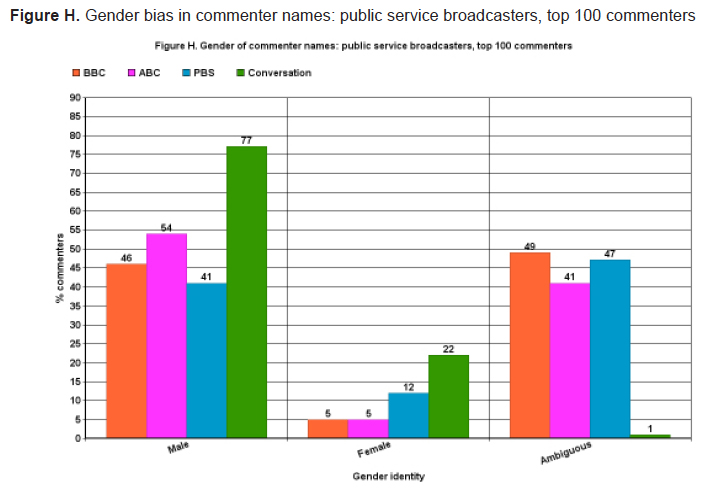

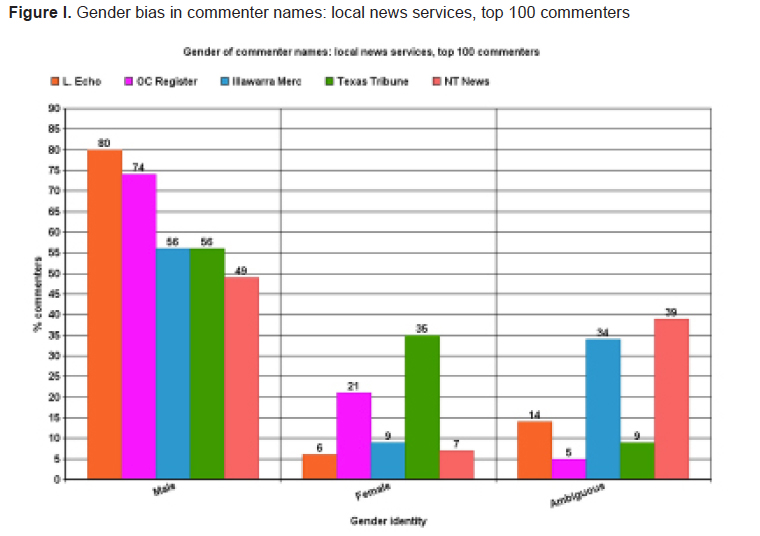

A more disturbing form of exclusion was noted in the content analysis of gendered user names among top 100 commenters. This indicates that very few commenters adopt female user names, even in real name commenting systems, and suggests that men dominate news commenting

The graphs below show, on the X axis, the division of users names by three categories: male, female and ambiguous (often pseudonymous, but also gender neutral), with the percentage of top 100 commenters on the Y axis.

Male-named participants dominate across all the international and metropolitan populations. All of the news services in this sample do have a male skew in their reported audience demographics, except the Daily Mail Online (55% F, 45% M), however the gender differentials seen here are far more pronounced. Across the board female-identified commenters represent a lower percentage of the news commenting population. In the two sites where pseudonyms are commonly used, The Guardian and The Washington Post, the representation of female user names is even lower (3% and 6%).

The real-name Facebook systems of the Texas Tribune (35%) Orange County Register (21%) and Huffington Post (20%), together with the real-name preferred Conversation (22%), represent the highest female participation rates. These figures correspond with those of a study of commenter gender identity in The New York Times, which found that 27.7% of gender identified commenters were women, and they made only 24.8% of the comments (Pierson, 2014).

The digital natives display the highest sectoral ratio of female identified participants. The Texas Tribune leads, despite its male target user skew, followed by the Huffington Post. The Daily Mail Online (17%), which has the fourth highest female identity ranking, has a pronounced female target user skew and “red-top”, or tabloid, focus on celebrity, human interest and lifestyle “soft” news, so it would be expected to perform higher. This suggests that news values, which have traditionally favored “hard,” or ostensibly masculine topics such as politics, crime, and sport and finance, are not a central factor determining the appeal of participation.

A similar pattern of male identity domination is obvious, and as consistent, amongst the public service broadcasters, the BBC, ABC and PBS. In Figure H, PBS demonstrates the highest female participation of the three but is the only service in this category to offer news rather than opinion commenting. As a group these services do not provide public data on their male/female audience skew, so considering its impact on participation is more difficult. The public broadcasters all enable pseudonymous participation so it is possible that they have a hidden female user group. However, a comparison with The Conversation, which encourages real-name participation, suggests that the male domination trend is still likely to be present.

Among the local sites the gender imbalance is also marked, particularly with the Liverpool Echo, a Trinity Mirror service that has a heavy focus on football and other sports coverage (6% female identified commenters). The Texas Tribune’s leading performance in female identified participation (35%) may be due to its third sector focus on public engagement and interest innnovation, and warrants further investigation for its site design, journalist involvement in comment facilitation, as well as its moderation and governance approaches. The Orange County Register, which has made a concerted public attempt to tackle incivility in commenting has achieved the second highest female identified interaction rate, contrasting with its reader demographics (47% F, 53% M). This indicates its move to real name Facebook commenting may be supporting gender inclusion better than other publications.

The Illawarra Mercury, the web presence of a regional print service covering the Wollongong area south of Sydney, and the Darwin-based state service Northern Territory News, both show a strong user preference for pseudonyms which may be important for commenting on contentious political issues in rural areas, to ensure privacy and social cohesion.

Overall the analysis suggests that there were very few users with female names, and thus that men dominate news commenting. The male bias, however, appears to be confirmed in the sites that demand real name use, via Facebook, such as the Huffington Post, PBS and Texas Tribune. Those sites with a strong culture of pseudonym use, The Guardian and the Huffington Post demonstrate even fewer declared female users, suggesting that the use of a gender ambiguous pseudonym is more desirable than the declaration of female identity.

Discussion

Aside from confirming the trend towards news media using social media as a preferred commenting platform, this study has made three interesting findings about access to participation in news commenting:

1. access to opinion commenting is higher than to news commenting

2. television broadcasters are less likely to host comments than newspapers

3. comment platform providers such as Facebook, Livefyre and Disqus are becoming key cultural intermediaries in in-house news participation

Future news participation research could usefully explore the value that users place on access to commenting on the news vis-a-vis opinion and analysis. In Weber’s (2013) study of factors influencing commenting, readers were more engaged by analysis than simple facticity. When Reuters recently shut down in-house comments on its news feeds (Reuters, 2014), but kept them on opinion and blogs sections of its site, it also appeared to be indicating the greater value of interaction around more discursive news forms. Dan Colarusso, the executive editor, provided an unconvincing case that social media were better commenting platforms because users were “well informed” and channels were “self-policed by participants to keep on the fringes those who would abuse the privilege of commenting” (Reuters, 2014).

This study suggests social media provide material accessibility and interaction, but are not “safe” or even necessarily desirable spaces for the discussion of contentious news issues. Governance issues are only now beginning to occupy Twitter, Facebook and YouTube as users demand greater facility for reporting and managing abusive behavior and removing offensive content.

Second, it is noteworthy that television broadcasters often rate as important news sources and yet their web services are less highly geared to access, interaction or participation than newspapers. This highlights how the print media’s circulation decline has been an impetus to greater reader engagement and points to this sector as a continuing focus for innovation in participative media, alongside public service and third sector media.

Thirdly, the rise of Facebook, Livefyre and Disqus as news mediation services merits further attention. There is little scholarship on the new cultural intermediaries of news journalism, and much to investigate about their relative power to aggregate, assemble and trade in user analytics, and thus potentially to influence editorial decision-making.

The comparative analysis of scale in news interaction demonstrates that the highest engagement sites all invest in deliberate participative strategies, which deserve closer study for their implementation of inclusive design and editorial practices. Support for pseudonymous commenting is also of interest in understanding social inclusion, particularly in rural areas where close social connections and proximity factors may otherwise inhibit users from making public comment on controversial topics.

The probable gender imbalance in news commenting was not completely unexpected. The findings here correspond, for example, with social studies of gendered participation in meetings and seminars where men control the organization of social spaces (Karpowitz & Mendelberg, 2014). However, it is critical to find out why women are not interacting through comments, and whether they find it unimportant, unappealing, costly or a lower priority than other social and cultural activities. Further research is needed to understand whether, and why, some women might adopt pseudonyms for the purposes of commenting on the news. One possible cause is the level of gender discrimination and abuse they may face in these forums, particularly in opinion sites, where the originating text is a polemic.

The likely gender bias of new commenting challenges naive conceptions of social inclusion in online media. It presents a challenge to journalists, moderators and the developers of commenting systems to think more deeply about the ways in which media participation is structured. For example, there has been some debate about whether the introduction of real name systems may deter participation, but in this instance real name systems show a greater visible presence of female identified participants than those that enable pseudonyms. While Pierson (2014) indicates this may not necessarily afford women greater social visibility in men’s eyes, it lends voice diversity to public debate.

Overall the study raises useful questions about the sole use of social media platforms for media participation and their diverse specific opportunities for the structuring of participation across different social and cultural groupings. Further as social media demand publicly identifiable, relationally bound interaction with news services, more investigation is needed on how users’ privacy and peer influence concerns impact on aspects of their access, interaction and participation.

Conclusion

The top 40 online news services studied here provide seemingly diverse forms of access to commenting on news and opinion, although more to the latter than the former. However, most news organizations have pushed their news participation out to branded social media channels with possible impacts on social inclusion. In-house commenting was less accessible, despite its economic, political and cultural value and greater guarantee of effective governance, and less common on broadcast news sites than those of newspapers. Public sector and subscription media impose limits on commenting access for economic and quality control reasons, suggesting research is needed into the editorial rationale for opening comments.

The trend to social commenting may reverse as companies seek more control over platform design and user analytics. The question then is whether the costs of producing in-house commenting outweigh the value of traffic and audience insights. Certainly the findings of gender bias in this study should make publishers and policy makers pause to investigate the commercial and diversity implications of this apparent marginalization of women from the digital public sphere.

This study suggests it takes more than social media to make for inclusive news participation. News journalism is a social environment where the focus on conflict and human drama engenders passionate responses; responses that reproduce, recirculate and amplify existing social inequities, fears and hatreds. If journalists are to establish participative ties to a wider range of users they will need to develop more sophisticated approaches to the design, facilitation and governance of commenting interactions. This invites further research on the design of systems for more inclusive news conversations, as well as new techniques for encouraging and mediating participation.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Aidan Wilson and Steven Hayes for their extensive work on the data capture, indexing and analysis; and to Dr. Marion McCutcheon for her help with the statistical analysis and visualization.

References

Anderson, C. (2006). The long tail: How endless choice is creating unlimited demand. London, UK: Random House Business Books.

Bintrim, R., Escarfuller, W., Sabatini, C., Tummino, A., & Wolsky, A. (2014). The Social Inclusion Index 2014. Americas Quarterly. Summer 2014. Retrieved from http://www.americasquarterly.org/charticles/socialinclusionindex2014/

Australian Government. (2013). Chapter 5: Multiculturalism and the social inclusion agenda. In Joint Standing Committee on Migration. Inquiry into Migration and Multiculturalism in Australia. March 2013. Canberra. Retrieved from http://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=mig/multiculturalism/report.htm

Barnes, R. (2014). The “ecology of participation”. Digital Journalism 2(4): 542-557.

Bartlett, J., Norrie, R., Pastel, S., Rumpel, R., & Wibberley, S. (2014). Misogyny on Twitter. Demos. Retrieved from http://www.demos.co.uk/publications/misogyny

Bentivegna, S., Guerrieri, P., & College of Europe. (2010). A composite index to measure digital inclusion in Europe: Analysis of e-Inclusion impact resulting from advanced R&D based on economic modelling in relation to innovation capacity, capital formation, productivity, and empowerment. European Commission. January 2010. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/news/composite-index-measure-digital-inclusion-europe-1st-part-study-analysis-e-inclusion-impact

Borger, M., van Hoof, A., Costera Meijer, I., & Sanders, J. (2013). Constructing participatory journalism as a scholarly object: A genealogical analysis. Digital Journalism 1(1): 117-134.

Braun, J., & Gillespie, T. L. (2011). Hosting the public discourse, hosting the public: When online news and social media converge. Journalism Practice 5(4): 383-398.

Brynjolfsson, E., Hu, Y. J., & Smith, M. D. (2010). The longer tail: The changing shape of Amazon’s distribution curve. Social Science Research Network. September 2010. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1679991

Cammaerts, B. & Carpentier, N. (2005). The unbearable lightness of full participation in a global context: WSIS and civil society participation. In J. Servaes & N. Carpentier (eds.), Towards a Sustainable Information Society: Beyond WSIS, (17-49). Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Carpentier, N. (2011). The concept of participation: If they have access and interact, do they really participate? CM: Communication Management Quarterly 21:13-36.

Editor’s note: Reader comments in the age of social media (2014, November 7). Reuters. Retrieved from http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2014/11/07/editors-note-reader-comments-in-the-age-of-social-media/Getting my two cents worth in: Access, interaction, participation and social inclusion in online news commenting 103

Ewart, J., & Snowden, C. (2012). The media’s role in social inclusion and exclusion. Media International Australia 142: 61-63.

Gillmor, D. (2004). We the media: Grassroots journalism by the people, for the people. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly.

Graham, T. (2013). Talking back, but is anybody listening: Journalism and comment fields. In Eds. C. Peters and M. Broersma, Rethinking journalism: Trust and participation in a transformed news landscape. Oxon, UK: Routledge. (114-128)

Griffin-Foley, B. (2004). From Tit-Bits to Big Brother: A century of audience participation in the media. Media, Culture & Society 26 (4): 533-48.

Hampton, K. N., Rainie, L., Lu, W., Dwyer, M., Shin, I., & Purcell, K. (2014). Social media and the ‘Spiral of Silence.’ Pew Research Center, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/08/26/social-media-and-the-spiral-of-silence/

Hare, K. (2014, December 8). St. Louis Post-Dispatch turns off comments on editorials. Why? Ferguson. Poynter.org Retrieved from http://www.poynter.org/news/mediawire/306609/st-louis-post-dispatch-turns-off-comments-on-editorials-why-ferguson/

Hollier, S. & Brown, J. (2014). Web accessibility implications and responsibilities: An Australian election case study. Paper presented at the Australian and New Zealand Communication Association Annual Conference, Swinburne University, Victoria, July 9-11. Retrieved from http://www.anzca.net/documents/2014-conf-papers/753-anzca14-hollier-brown/file.html

Innovation. (2014, March 24). The New York Times. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/nyt_innovation_2014

Khan, H. I., M. & Bawany, N.S. (2014). Web accessibility evaluation of news websites using WCAG 2.0. Research Journal of Recent Sciences 3(1): 7-13. Retrieved from http://www.isca.in/rjrs/archive/v3/i1/2.ISCA-RJRS-2013-234.pdf

Karpowitz, C. F. & Mendelberg, T. (2014). The silent sex: Gender, deliberation, and institutions. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Martin, F. (2012) Vox Populi, Vox Dei: ABC Online and the risks of dialogic interaction. In M. Burns & N. Brugger (eds.), Histories of public service broadcasters on the web, (177-192). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Newman, C. (2014, April 12). Sick of Internet comments? Us, too — Here’s what we’re doing about it. Voices. [Blog post] Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved from http://voices.suntimes.com/news/sick-of-web-comments-us-too-heres-what-were-doing-about-it/

Newman, N. & Levy, D.A. (2014). Reuters digital news report 2014. Reuters Institute for Journalism. Retrieved from http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/

Penman, R. & Turnbull, S. E. (2012). Socially inclusive processes: New opportunities with new media? Media International Australia 142: 74-86

Pierson, E. (2014). Outnumbered but well-spoken: Female commenters in the New York Times. Paper presented to CSCW 2015. Vancouver, March 14-18. Retrieved from http://cs.stanford.edu/people/emmap1/cscw_paper.pdf

Singer, J., Domingo, D., Heinonen, A., Hermida, A., Paulussen, A., Quandt, T., Reich, Z., & Vujnovic, M. (2011) Participatory journalism: Guarding open gates at online newspapers. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sonderman, J. (2012, October 22). How the Huffington Post handles 70+ million comments a year. Poynter.org. Retrieved from http://www.poynter.org/news/mediawire/190492/how-the-huffington-post-handles-70-million-comments-a-year/

Turner, H. (2013, June 21). Report for Ofcom: The value of user-generated content. [Consultants report,. Retrieved from http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/research-publications/content.pdf

Trygg, S. (2012). Is comment free? Ethical editorial and ethical problems of moderating online news. London, UK: Journalist Fonden/Polis. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/files/2012/01/IsCommentFree_PolisLSETrygg.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (2014). Racial and ethnic equality and social inclusion. [Policy brief]. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/p/wha/rt/social/

Van Dijk, J. (2008). One Europe, digitally divided. In A. Chadwick & P. N. Howard (Eds.), The handbook of Internet politics. (288-304). London and New York: Routledge.

Viner, K. (2013, October 9). The rise of the reader: Journalism in the age of the open web. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/09/the-rise-of-the-reader-katharine-viner-an-smith-lecture

Weber, P. (2014) Discussions in the comments section: Factors influencing participation and interactivity in online newspapers’ reader comments. New Media & Society 16(6): 941-957

World Editors Forum. (2013). Online comment moderation: Emerging best practices. World Association of Newspapers, WAN-IFRA and Open Society Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.wan-ifra.org/reports/2013/10/04/online-comment-moderation-emerging-best-practices

Fiona Martin is a Discovery Early Career Research fellow studying digital media policy and industry change, and lecturing in online journalism at the Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney. Martin is a former journalist/producer with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and has worked in radio, print and online media. She is editor and author of The Value of Public Service Media (Nordicom, 2014), and a contributor to Ethics for Digital Journalists (Routledge, 2014). Her Australian Research Council-funded project, Mediating the Conversation, investigates inclusive approaches to hosting public comments on news and opinion websites. She tweets @media_republik.

One thought on “Getting my two cents worth in”